Boaz Levin is a writer, curator, and occasional filmmaker based in Berlin. In his research and writing, Levin explores relations between politics, technology, and the environment. Levin is the co-founder, together with Vera Tollmann and Hito Steyerl, of the Research Center for Proxy Politics. In 2017, he was co-curator of the Biennale für Aktuelle Fotografie, which is staged at exhibition venues in Heidelberg, Mannheim, and Ludwigshafen. In 2021, he co-curated the 3rd Chennai Photo Biennale. In 2022, he curated, together with Esther Ruelfs, Mining Photography: The Ecological Footprint of Image Production (MK&G, Hamburg, KunstHausWien, and Gewerbemuseum Winterthur). He is the author of On Distance, ed. Laura Preston (Berlin: Atlas Projectos, 2020).

Levin is editor of Cabinet Magazine's Kiosk platform.

[I]n its timeliness and historical depth, Mining Photography provides a much-needed corrective to many blind spots of production in the consumer economy.

Eva Diaz, Aperture Magazine.

Eine bedeutende Ausstelung, die wunde Punkte berührt.

Carolin Förster, Camera Austria

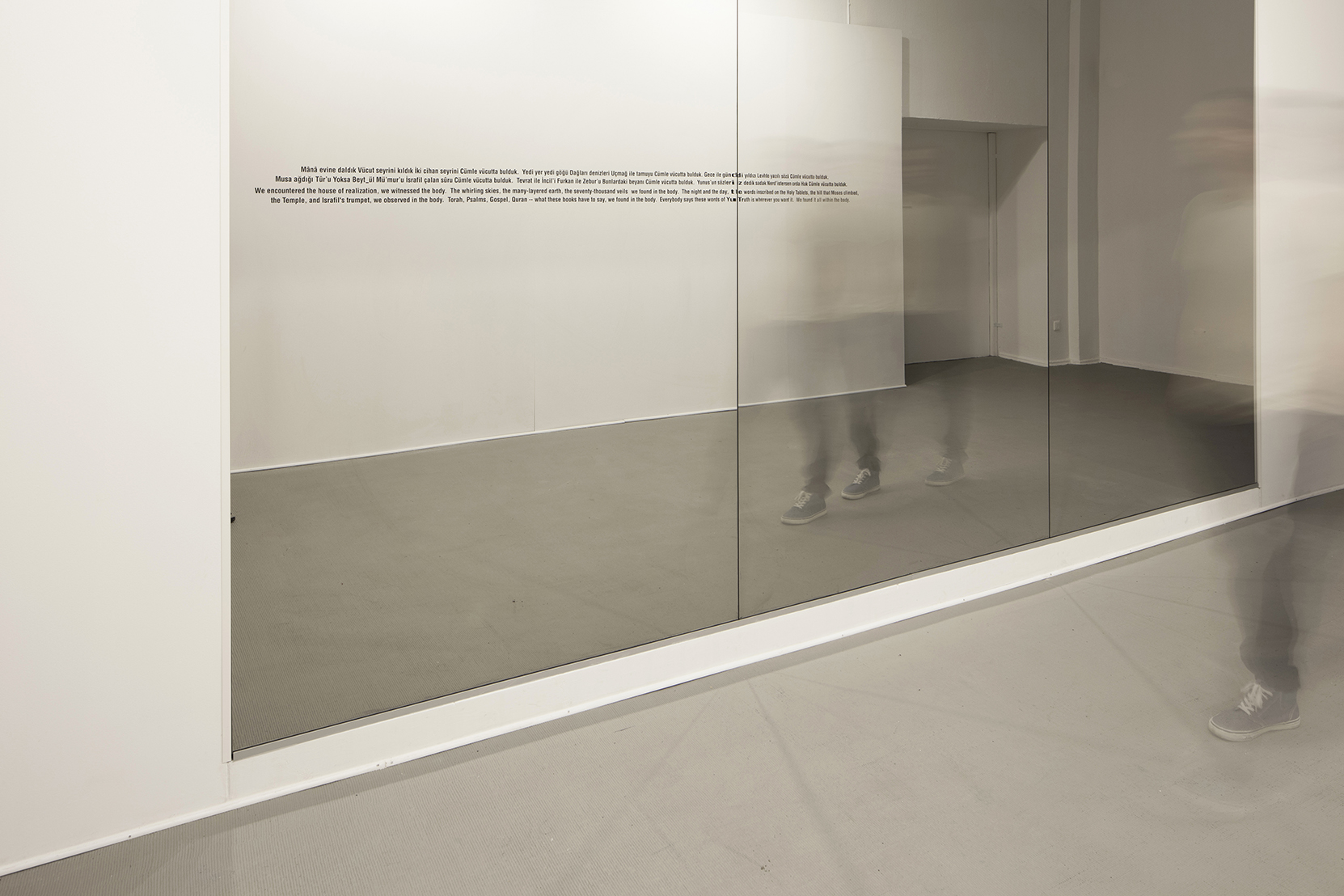

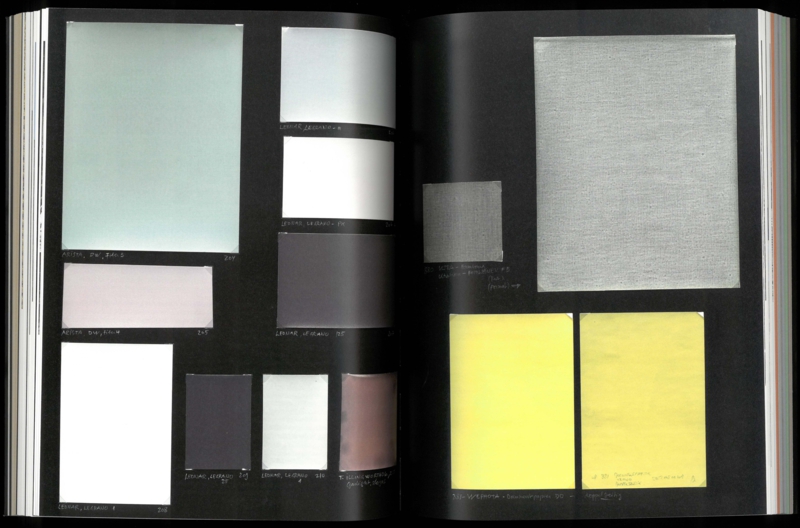

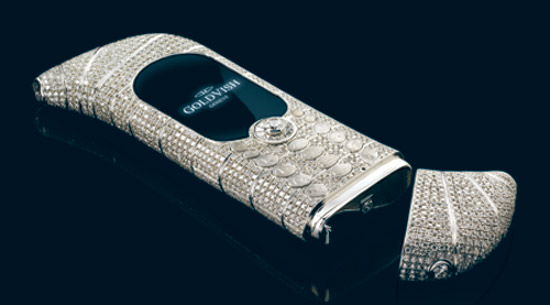

Ever since its invention, photography has depended on the global extraction and exploitation of so-called natural resources. In the early 19th century, these were salt, fossil fuels such as bitumen and carbon, as well as copper and silver, which were all used for the first images on copper plates and for salt paper prints. By the late 20th century, the photographic industry was one of the most important consumers of silver, responsible, at its peak, for more than half of the metal’s global consumption. Today, with the advent of digital photography and the ubiquity of mobile devices, image production is contingent on rare earths and metals such as coltan, cobalt, and europium. Image storage and distribution also consume immense amounts of energy. One scholar recently observed that Americans produce more photographs every two minutes than were made in the entire nineteenth century. "Mining Photography: The Ecological Footprint of Image Production" is dedicated to the material history of key resources used for image production, addressing the social and political context of their extraction and waste and its relation to climate change. Using historical photographs and contemporary artistic positions as well as interviews with restorers, geologists, and climate researchers, the exhibition tells the story of photography as one of industrial production, showing the extent to which the medium has been deeply intertwined with the human change of the environment. By focusing on the ways by which industrial image production has been materially and ideologically implicated in climate change, rather merely using it to depict its consequences, the exhibition employs a radically new perspective towards this subject.

Participating artists: Ignacio Acosta, Lisa Barnard, F& D Cartier, Optics Division of the Metabolic Studio (Lauren Bon, Tristan Duke, Richard Nielsen), Klasse Digitale Grafik HFBK (Mari Lebanidze, Cleo Miao, Leon Schwer und Marco Wesche), Susanne Kriemann, Mary Mattingly, Daphné Nan Le Sergent, Lisa Rave, Alison Rossiter, Robert Smithson, Simon Starling, Anaïs Tondeur, James Welling, Noa Yafe, Tobias Zielony

The exhibition is curated by artist, author and curator Boaz Levin and Dr. Esther Ruelfs, Head of the Photography and New Media Collection at MK&G. In cooperation with Kunsthaus Wien, Gewerbemuseum Winterthur and the HFBK Hamburg.

An exhibition kindly supported by the Alfried-Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach Stiftung, the NUE Foundation (North German Foundation for Environment and Development) from proceeds of BINGO! Die Umweltlotterie, by Pro Helvetia, Artis and the Institut français Deutschland.

Media partner: ARTE

Link to program

Link to program

BPA at Gropius Studios resonates with the history of the Gropius Bau, which opened in 1881 as a Museum and School of Decorative Arts featuring numerous studios and workshops. The project offers artists physical space for their work in the Gropius Bau building, thereby re-establishing the institution as a place of artistic production, and blurring the boundaries between studio and exhibition space. With the rooms being utilised for both creative work and different presentation formats, BPA at Gropius Studios asks what it means for artists to reveal parts of their artistic process and to invite an audience into their studio.

In addition to returning to the historical roots of the building, the collaboration also aims to open the exhibition hall to partners in the city and to provide a platform for Berlin artists together with BPA. BPA // Berlin program for artists was founded in 2016 by artists Angela Bulloch, Simon Denny and Willem de Rooij, facilitating exchange between emerging and established Berlin-based artists. The mentoring programme organises reciprocal studio visits, public lectures and joint exhibitions.

The programme is curated by Boaz Levin and Anna-Lisa Scherfose (Assistant Curator) and supported by the Senate Department for Culture and Europe.

Participating artists

Nadja Abt, Niklas Binzberger, Rob Crosse, Anne Fellner, Bertrand Flanet, Dina Khouri, Doireann O'Malley, Victor Payares, Esper Postma, Anton Steenbock, Katrin Winkler

Programme

1.10.20, 16:00–20:00

BPA Talks 3

With Anne Fellner, Bertrand Flanet, Katrin Winkler and BPA mentors Calla Henkel & Max Pitegoff

Gropius Bau, Cinema

In partnership with KW Institute for Contemporary Art

22.–28.10.20

BPA at Gropius Studios – public presentation

Dina Khouri, Katrin Winkler

5.–11.11.20

BPA at Gropius Studios – public presentation

Rob Crosse, Bertrand Flanet, Doireann O’Malley

26.11.–2.12.20

BPA at Gropius Studios – public presentation

Victor Payares, Esper Postma, Anton Steenbock

17.–23.12.20

BPA at Gropius Studios – public presentation

Michelle Volta, Niklas Binzberger, Anne Fellner

Co-curated with Tobias Zielony

Lia Rumma Gallery, Napels

19 June - 26 July 2019

Featuring: Yalda Afsah, Sohrab Hura, Gwen Smith and Tobias Zielony

Co-curated with Tobias Zielony

Lia Rumma Gallery, Napels

19 June - 26 July 2019

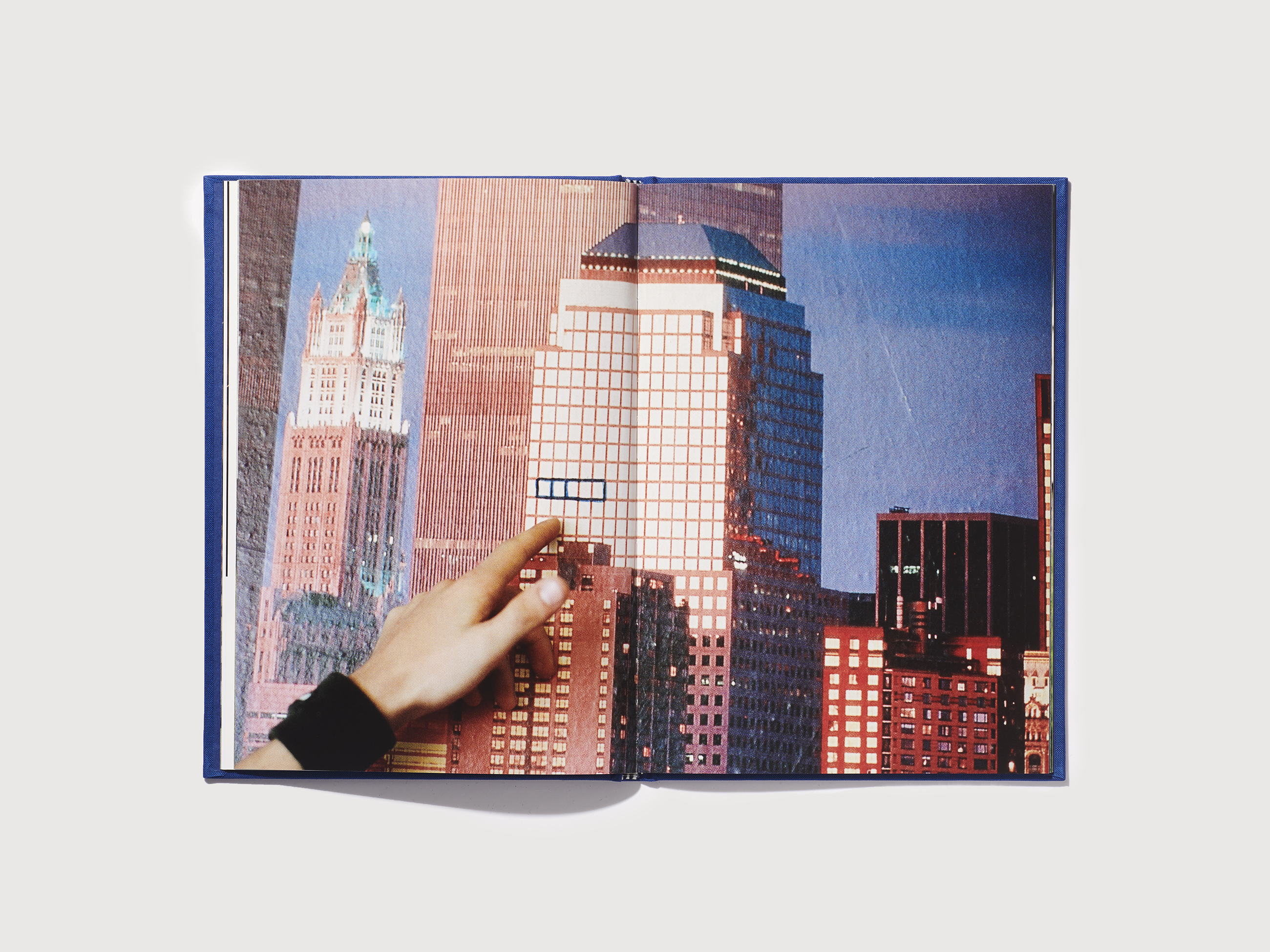

Of a Fire on the Moon takes its title from Norman Mailer’s book documenting the Apollo 11 1 moon landing and brings together four artists whose2 work stands at the intersection between realism and estrangement. Nocturnal, these works seem to view their subjects through flashes and flickers, or dream-like and distant.

Gwen Smith’s Fuck, Cook2, Look: the first and last time I remember being in Naples (1993/2017) juxtaposes a series of silver gelatin black and white images from 1993, taken during the artist’s first visit to the city, with color inkjet prints from her most recent trip. The images become mnemonic devices, highlighting the changing nature of photography with the transition from analog to digital, leading to ever more instantaneous archiving.

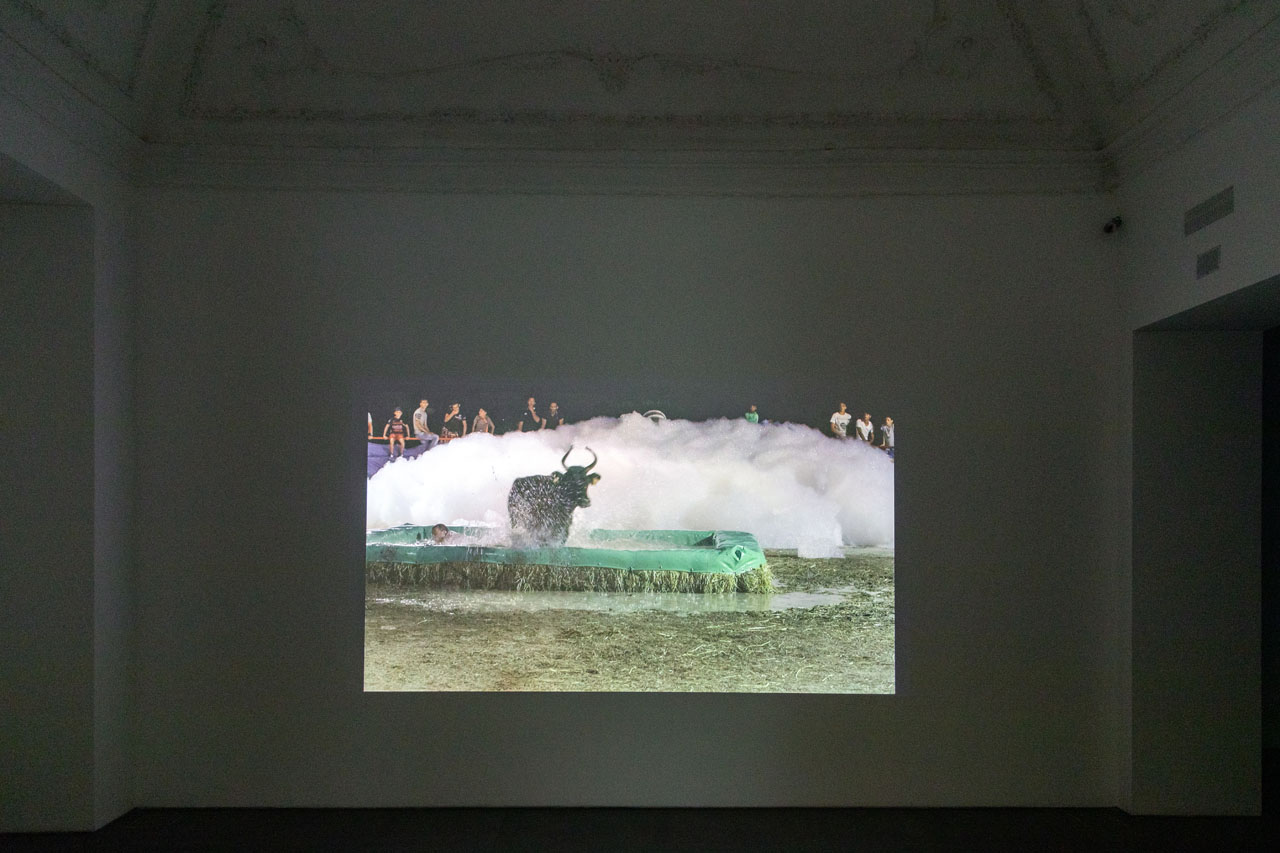

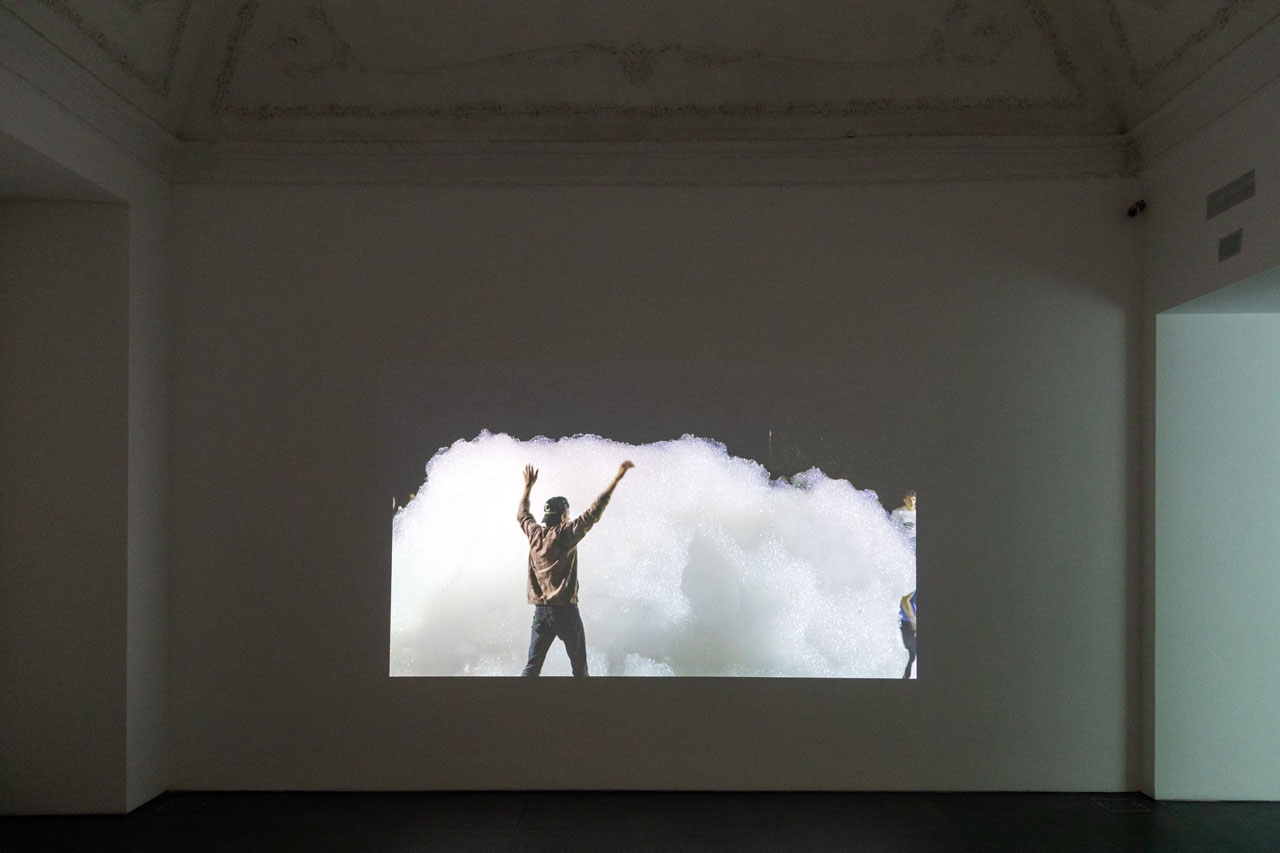

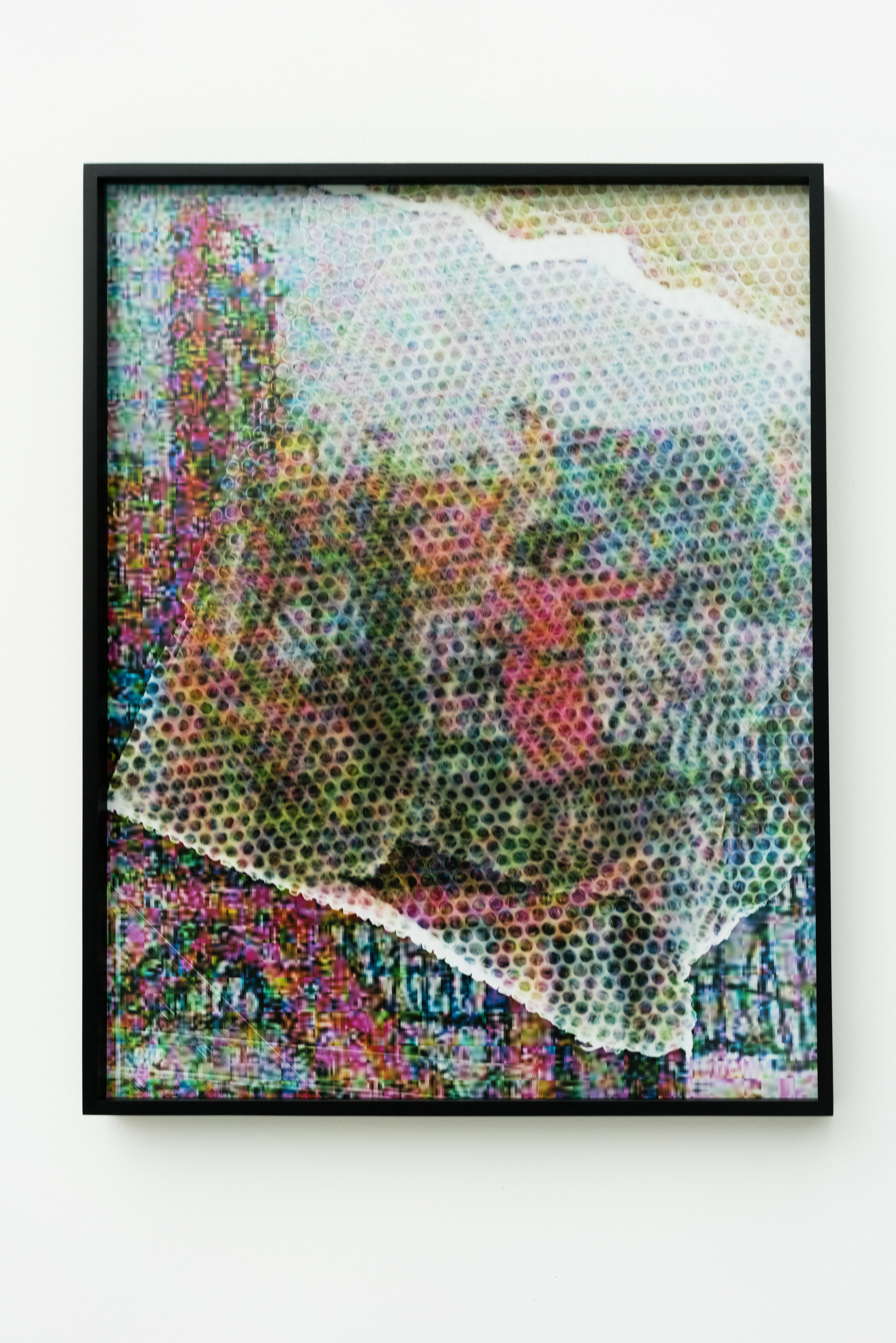

A cloud of thick foam floats across a dark arena, artificially lit. For a moment, time seems to be suspended, and sounds—of running and panting, the scraping of hoofs, of splashing, spraying, lunging—are heightened. Yalda Afsah’s video Tourneur (2018) documents a bullfight in the south of France that becomes a stage for a strange performance of masculinity and animality. Bubbles envelope both the teenagers and the bull they pursue, becoming a screen through which the scene is revealed, and concealed. At once realistic and relentlessly contrived, Tourneur becomes a ritualistic experiment in representation and its dissolution.

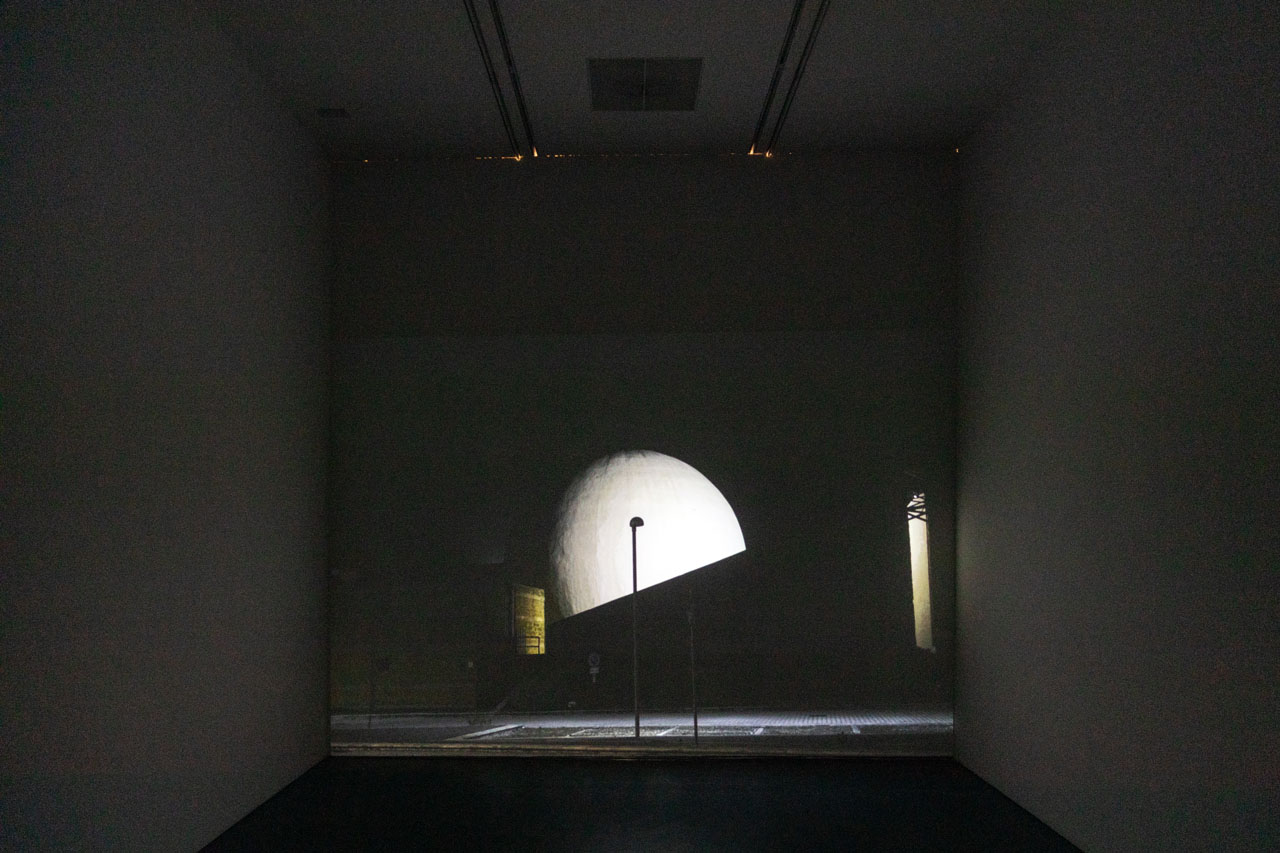

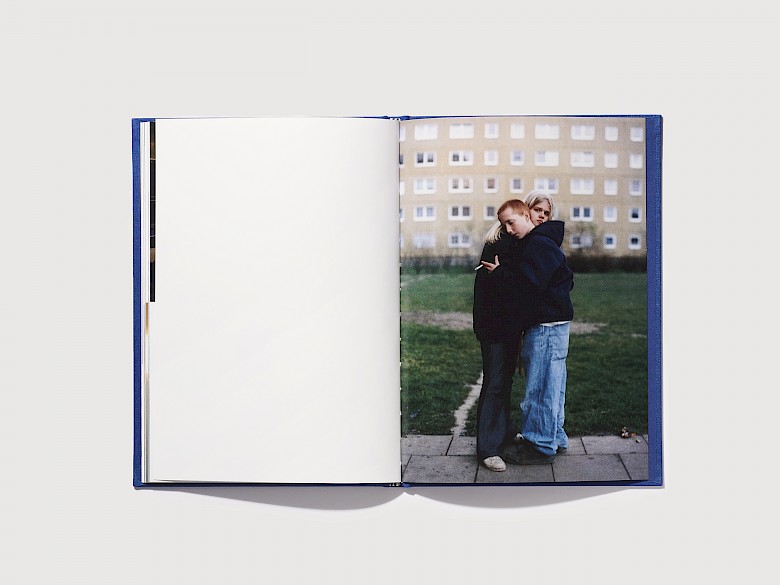

In Tobias Zielony’s photo animation A Fire on the Moon (2019) rather than outer space, here we viewers are sent to Gibellina—the Sicilian town destroyed by the Belice earthquake in 1968, a year before the Apollo 11 mission—now a ghost town, where Ludovico Quaroni’s large concrete orb shaped church, the Chiesa Madre, looms large. Through the darkness and flicker of Zielony’s stop-motion sequence we find a city as-if frozen, now animated. Reminiscent of both early experiments in cinematic illusionism such as Georges Méliès ‘A Voyage to the Moon’, as well as Italian Neo-Realism’s post-war urban social portraits, in on the moon fact and fiction, illusion and document, seem to converge.

Sohrab Hura’s video The Lost Head & The Bird (2019) explores life at the extremities of Indian society through an explosive profusion of images and stories, facts and fictions. Employing a dizzying montage of excess, alternating between absurdity and abjection, his work tests the thresholds of legibility and affect. Violence lurks as a constant undercurrent—of caste, sex, religion, political alliance—erupting with increasing frequency and virulence.

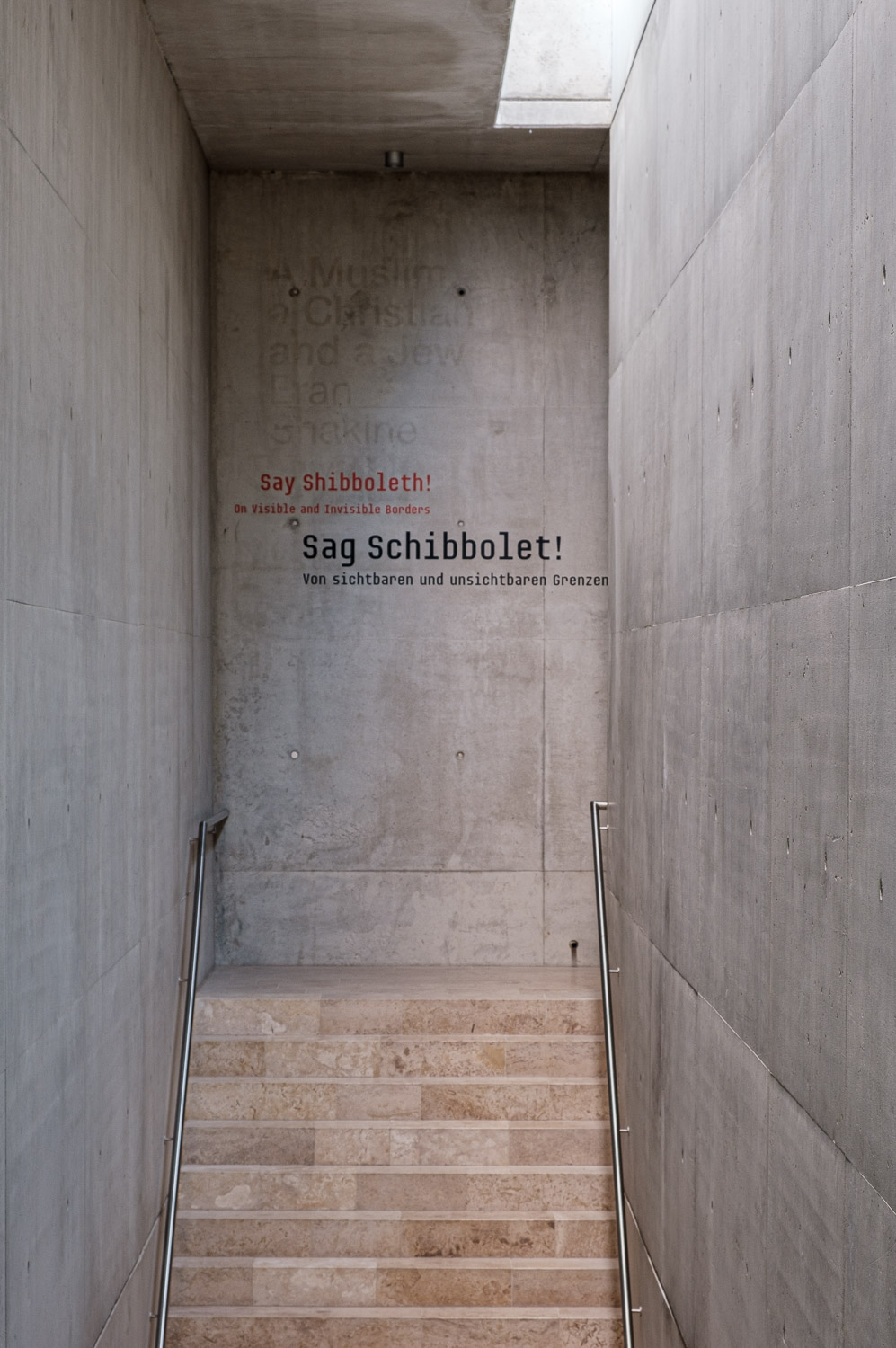

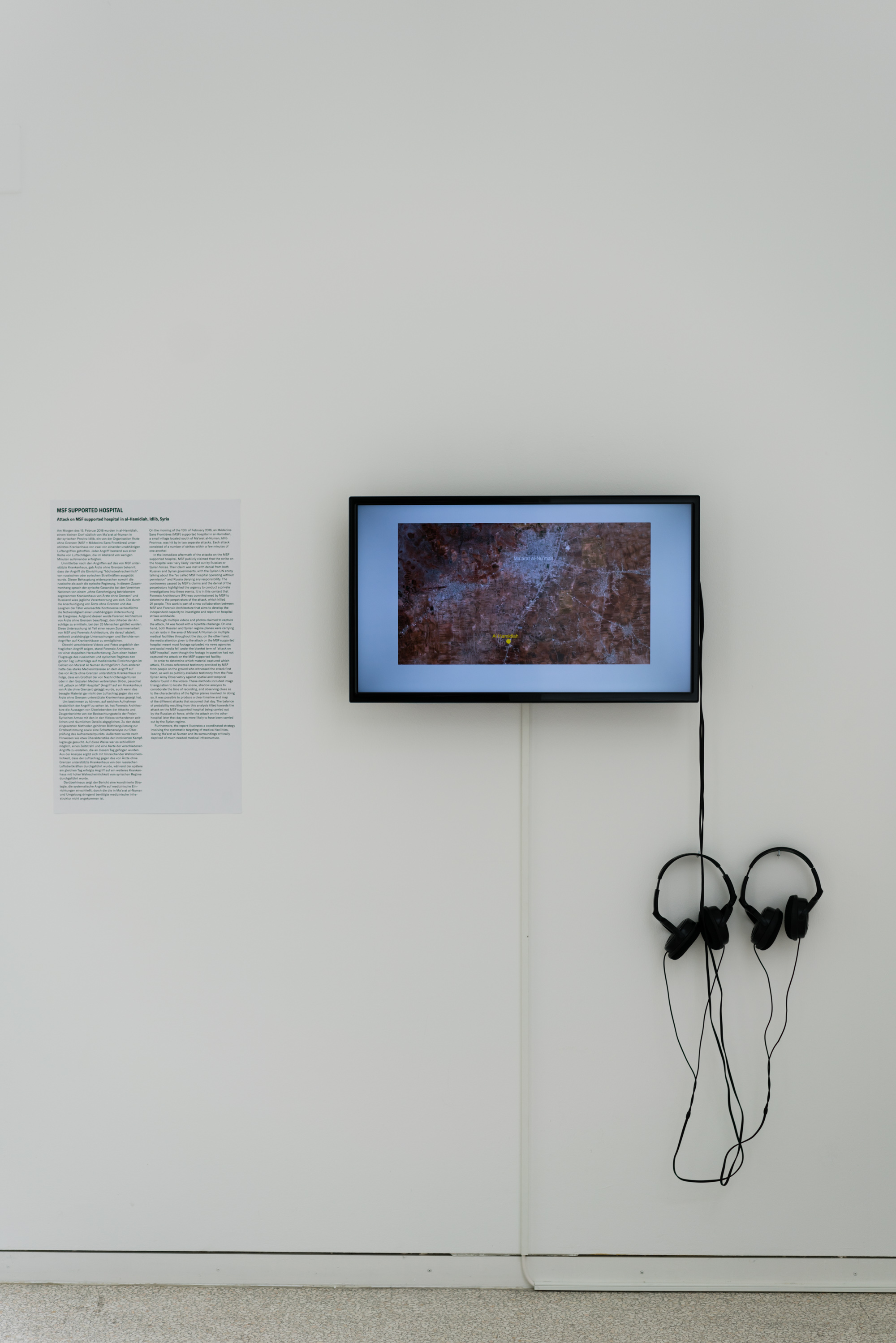

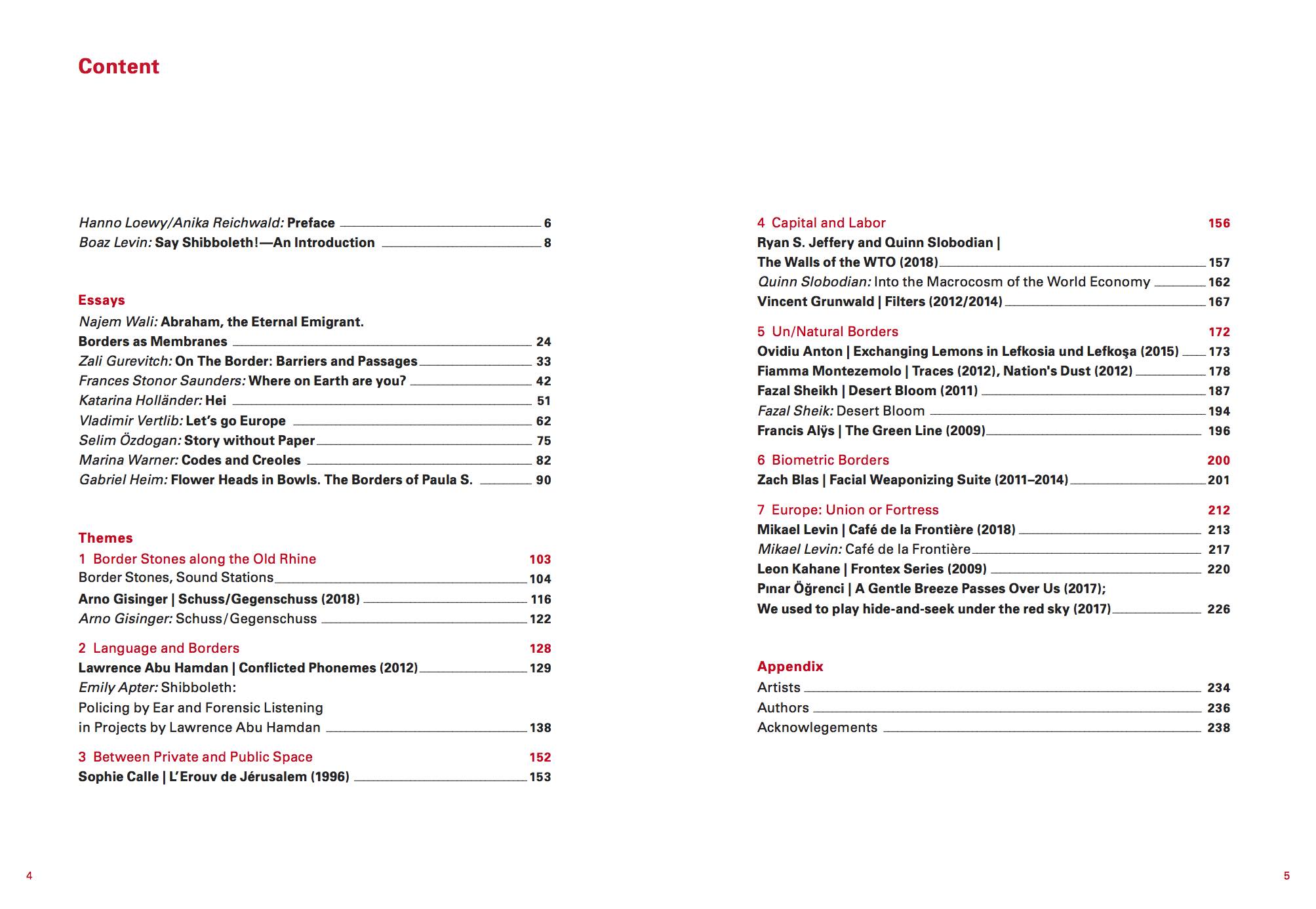

An exhibition by the Jewish Museum Hohenems

In collaboration with the Jewish Museum Munich

May 29th 2019 – February 23rd 2020

Ovidiu Anton, Zach Blas, Sophie Calle, Caroline Bergvall, Arno Gisinger, Vincent Grunwald, Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Ryan S. Jeffery and Quinn Slobodian, Leon Kahane , Mikael Levin, Fiamma Montezemolo, Pīnar Öğrenci, Fazal Sheikh

An exhibition by the Jewish Museum Hohenems

In collaboration with the Jewish Museum Munich

May 29th 2019 – February 23rd 2020

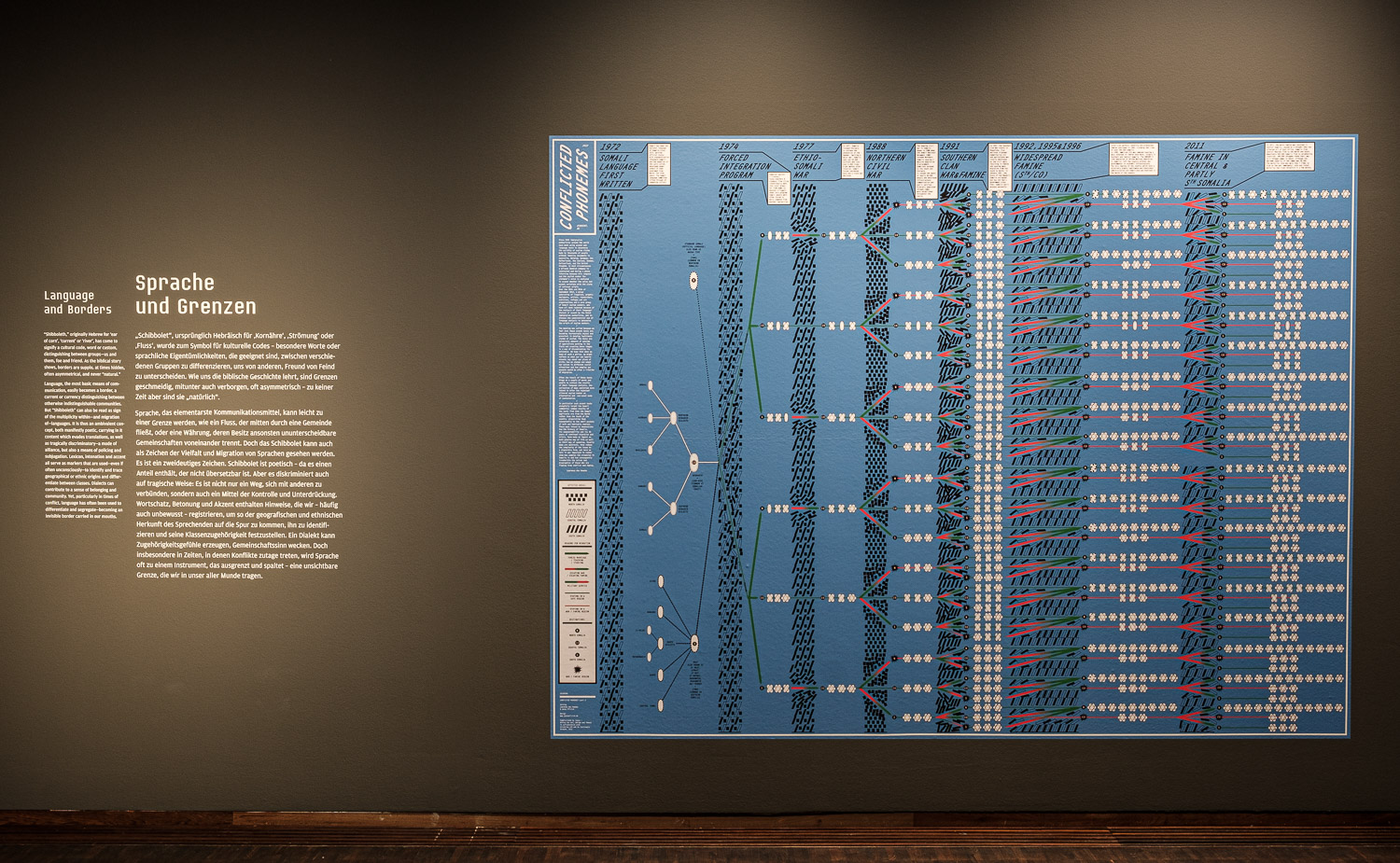

The Gileadites captured the fords of the Jordan opposite Ephraim. And it happened when any of the fugitives of Ephraim said, “Let me cross over,” the men of Gilead would say to him, “Are you an Ephraimite?” If he said, “No,” then they would say to him, “Say now, ‘Shibboleth.’” But he said, “Sibboleth,” for he could not pronounce it correctly. Then they seized him and slew him at the fords of the Jordan. Thus there fell at that time 42,000 of Ephraim.“ (Judges 12:5,6)

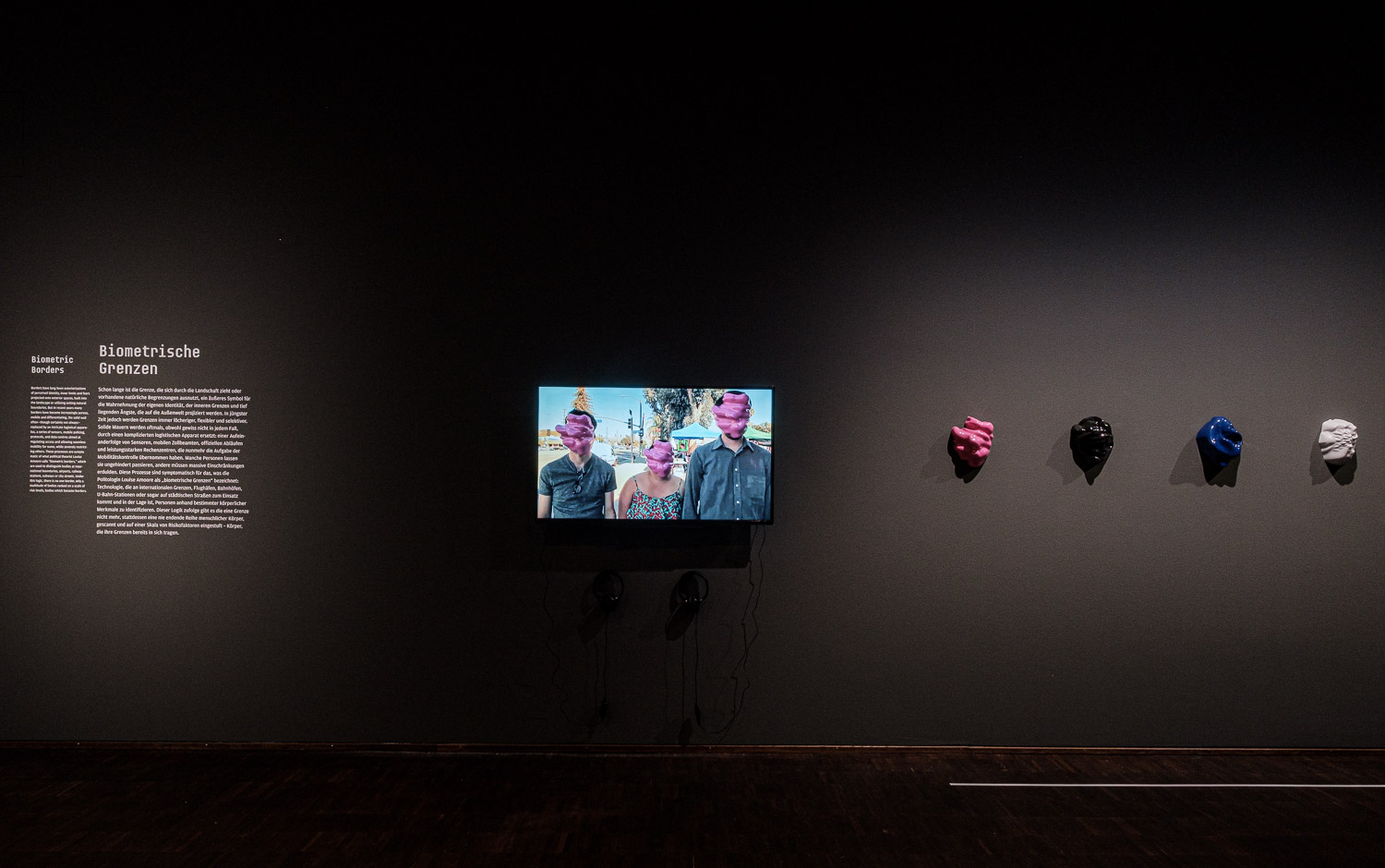

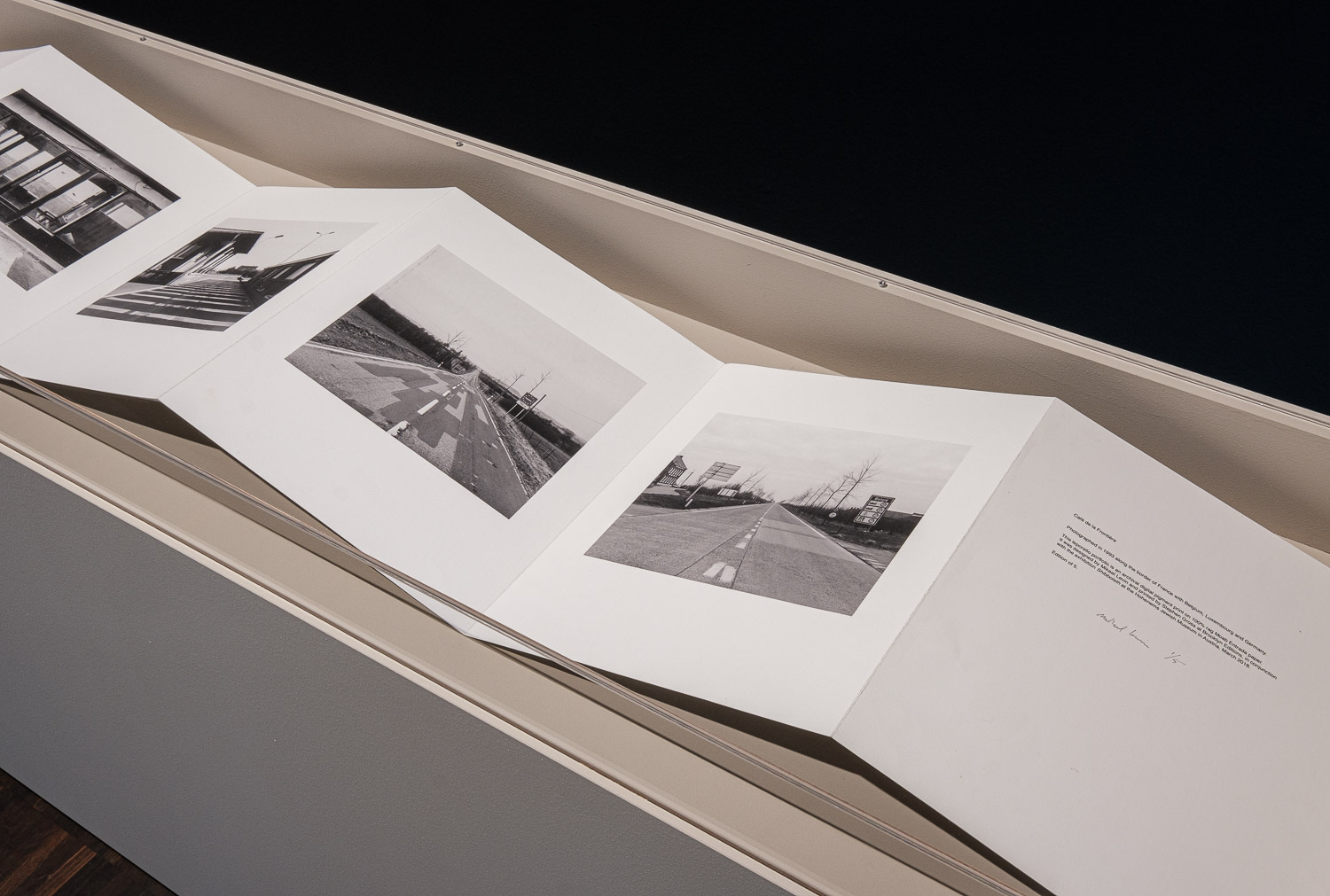

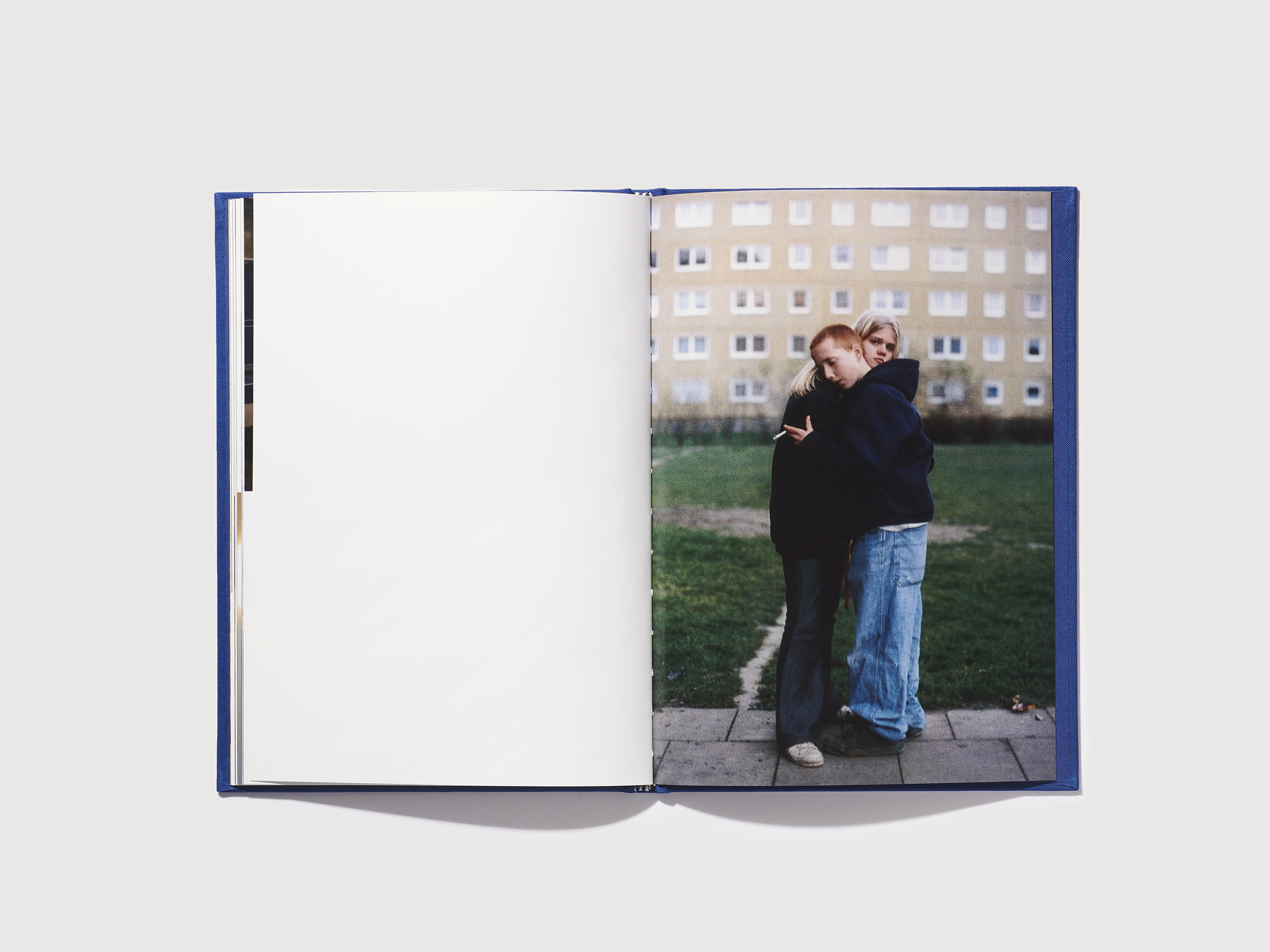

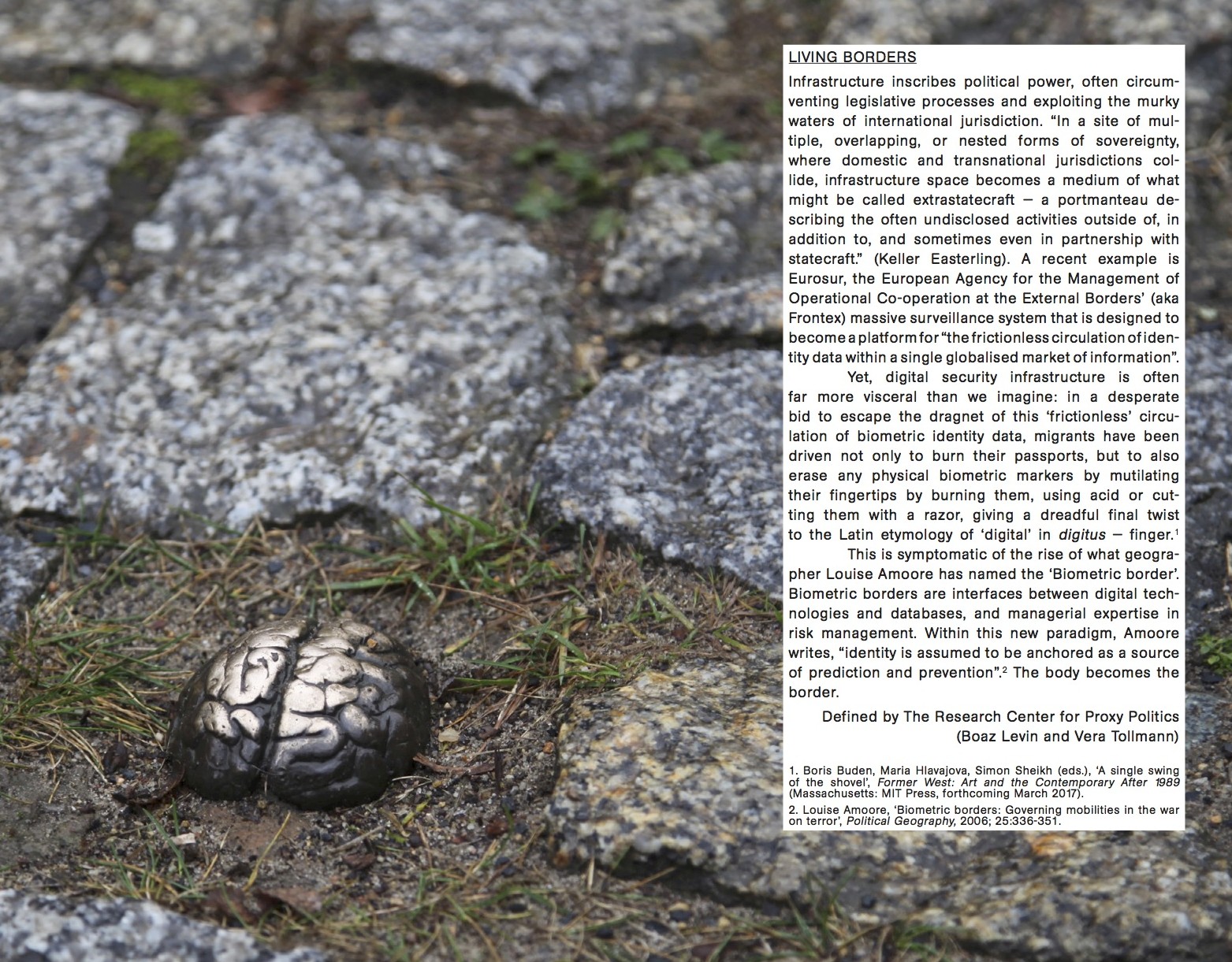

Despite talk about globalization and international community, new borders, fences, and walls are erected all over the world—around states, occupied territories, and gated communities, between public and private spaces, between the legal and the illegal. Some of these borders are permeable and others fatal, some are visible and others reinforced by cultural codes, language tests, or biometric methods. Borders decide about life and death, “identity” and “otherness”, belonging and exclusion.

Starting from the biblical story of the Ephraimites‘ escape from the victorious Gileadites and its failing on the banks of the River Jordan, the Jewish Museum Hohenems has invited international artists to critically reflect upon borders—just a stone’s throw away from the banks of the “Old Rhine,” the river where in 1938 refugees tried to reach Switzerland. Today, though, the presence of these refugee dramas has been pushed to the edges of our awareness.

An exhibition by the Jewish Museum Hohenems

In collaboration with the Jewish Museum Munich

05/2018 – 02/2019 Hohenems

Ovidiu Anton, Zach Blas, Sophie Calle, Caroline Bergvall, Arno Gisinger, Vincent Grunwald, Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Ryan S. Jeffery and Quinn Slobodian, Leon Kahane , Mikael Levin, Fiamma Montezemolo, Pīnar Öğrenci, Fazal Sheikh

An exhibition by the Jewish Museum Hohenems

In collaboration with the Jewish Museum Munich

05/2018 – 02/2019 Hohenems

The Gileadites captured the fords of the Jordan opposite Ephraim. And it happened when any of the fugitives of Ephraim said, “Let me cross over,” the men of Gilead would say to him, “Are you an Ephraimite?” If he said, “No,” then they would say to him, “Say now, ‘Shibboleth.’” But he said, “Sibboleth,” for he could not pronounce it correctly. Then they seized him and slew him at the fords of the Jordan. Thus there fell at that time 42,000 of Ephraim.“ (Judges 12:5,6)

Despite talk about globalization and international community, new borders, fences, and walls are erected all over the world—around states, occupied territories, and gated communities, between public and private spaces, between the legal and the illegal. Some of these borders are permeable and others fatal, some are visible and others reinforced by cultural codes, language tests, or biometric methods. Borders decide about life and death, “identity” and “otherness”, belonging and exclusion.

Starting from the biblical story of the Ephraimites‘ escape from the victorious Gileadites and its failing on the banks of the River Jordan, the Jewish Museum Hohenems has invited international artists to critically reflect upon borders—just a stone’s throw away from the banks of the “Old Rhine,” the river where in 1938 refugees tried to reach Switzerland. Today, though, the presence of these refugee dramas has been pushed to the edges of our awareness.

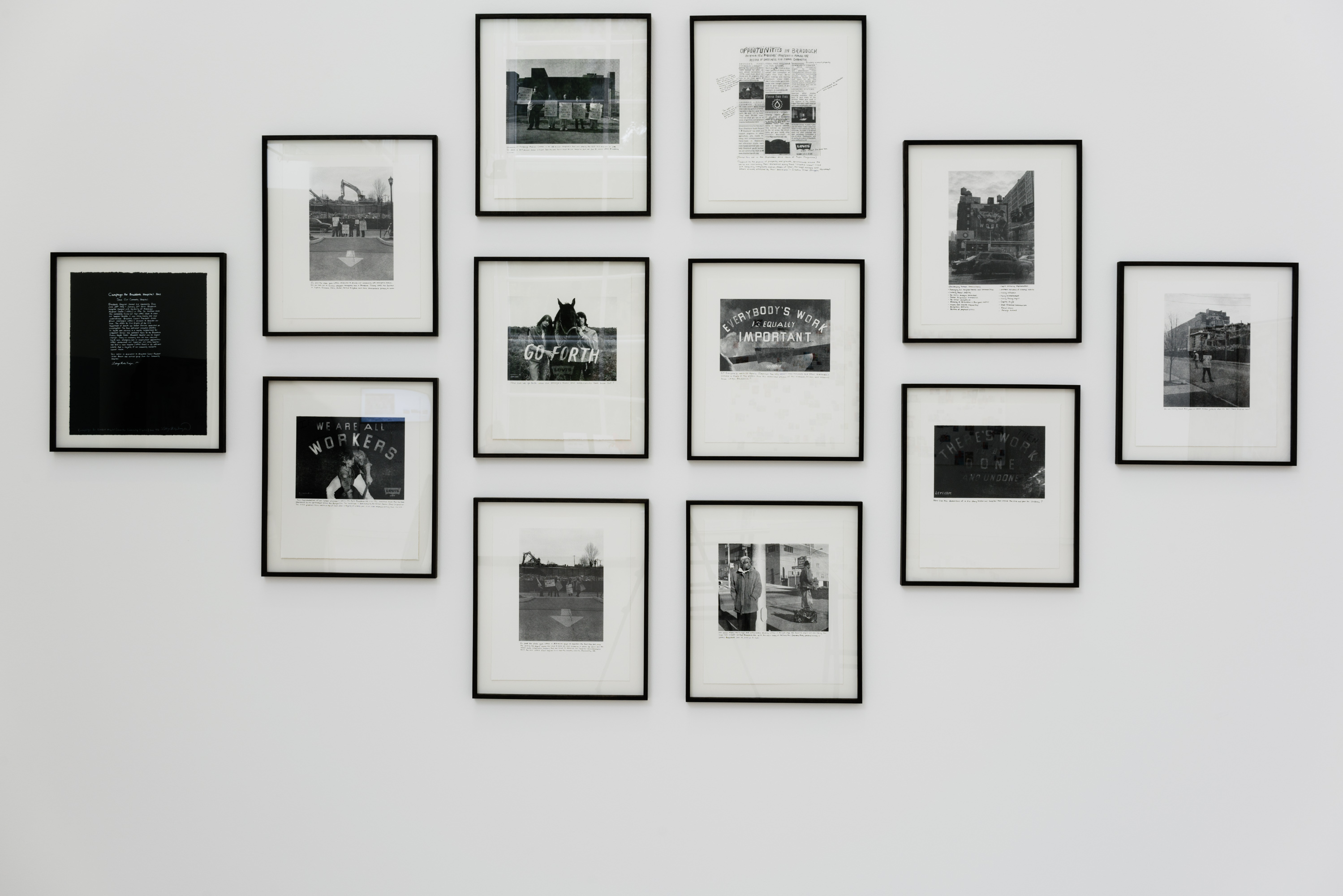

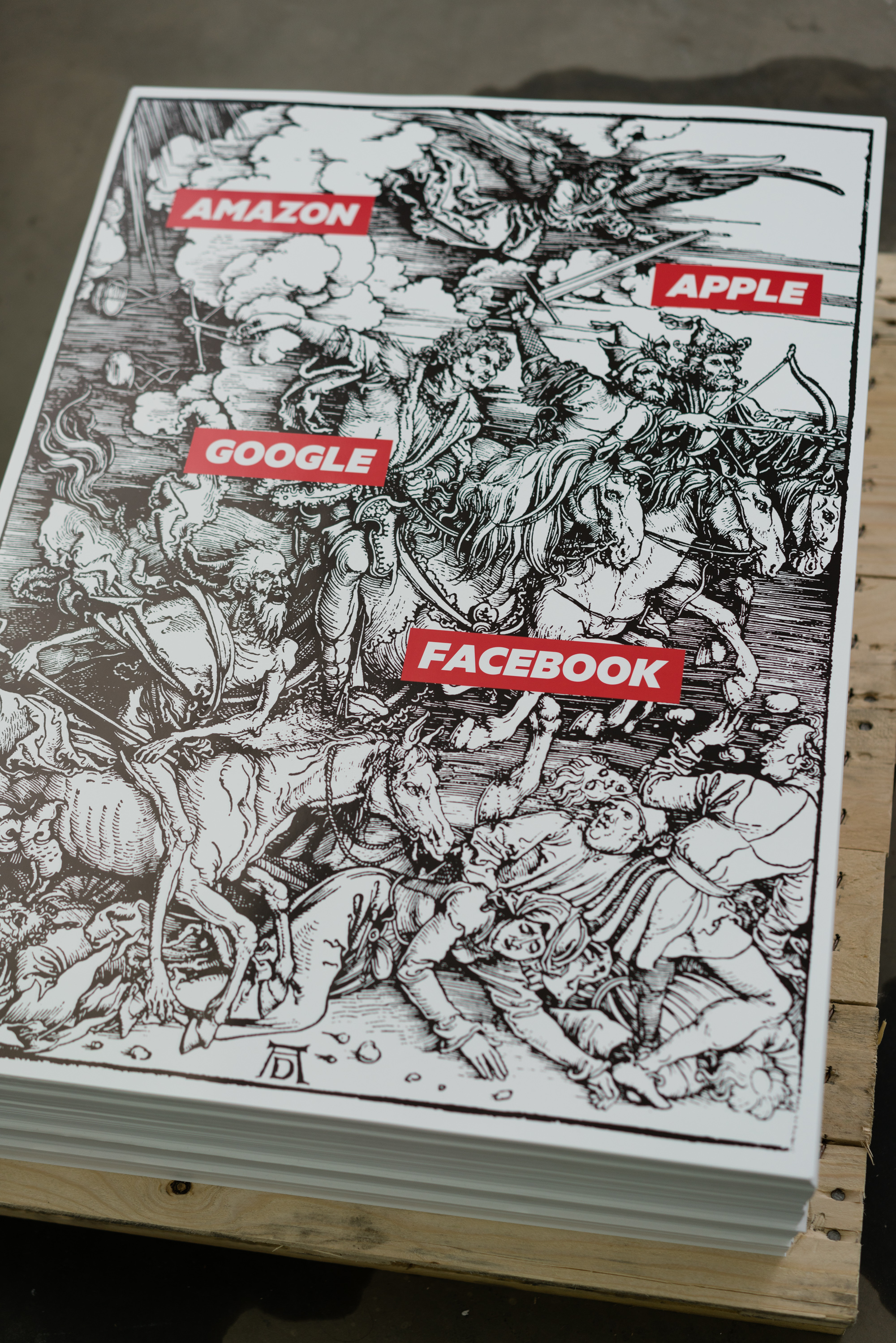

Farewell Photogrpahy

Mannheim-Ludwigshafen-Heidelberg

09/09-05/11 2017

Kunstverein Heidelberg

With works by: Forensic Architecture, Richard Frater, LaToya Ruby Frazier, John Heartfield, Nikita Kadan, Merle Kröger & Philip Scheffner, Fred Lonidier, Naeem Mohaiemen, Willem de Rooij, belit sağ, D. H. Saur, Mark Soo, Klaus Staeck, Oraib Toukan

Farewell Photogrpahy

Mannheim-Ludwigshafen-Heidelberg

09/09-05/11 2017

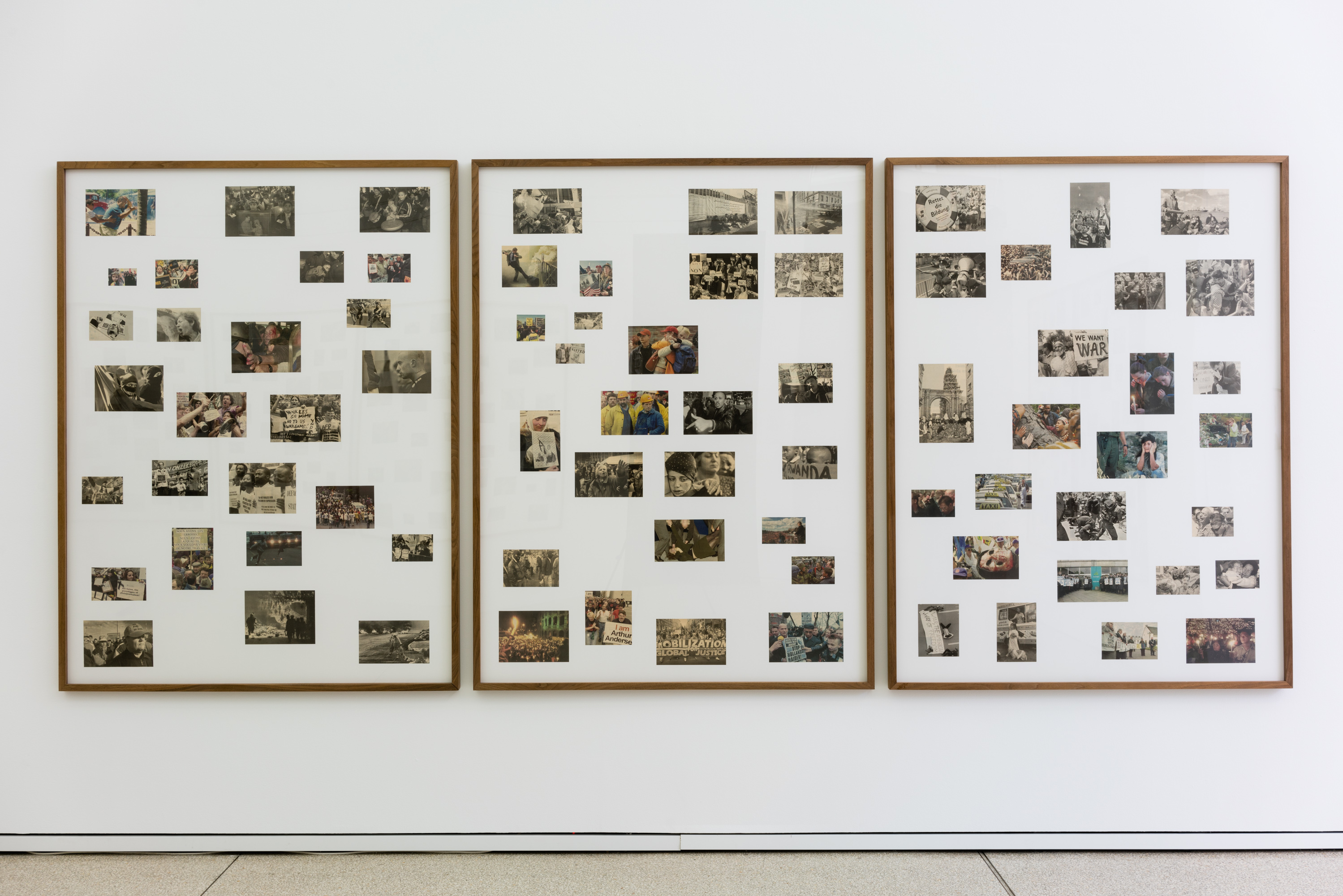

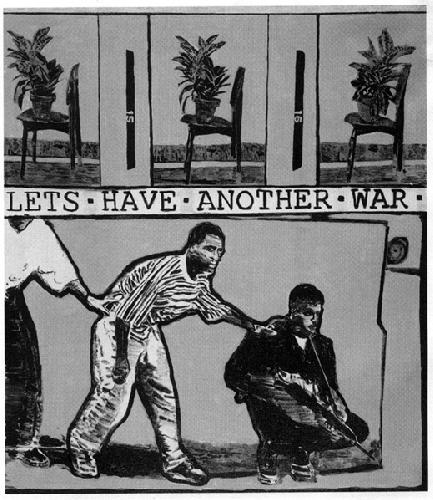

More than one hundred fifty years after its invention, photography’s presence in the political sphere is today as contentious as ever. Its unique ability not only to render people and places beyond our immediate experience visible, but also to lend them new meaning, has often placed photography at the heart of political debates. Still images are better retained by memory, and despite the omnipresence of instantaneous “live” video documentation, iconic images—images that circulate extensively whose mark remains etched in our collective memory—are more likely to be still photographs. Since it first emerged, photography has been either heralded for its emancipatory and civic potential—it’s capacity, in the words of nine teenthcentury abolitionist Frederick Douglass, to enable “men of all conditions [to] see themselves as others see them”—or derided and criticised as manipulative, crude and objectifying, as a mechanism of control, surveillance, and classi cation. At the advent of the digital age, the expanding scope, breadth and speed of image dissemina tion has made the question of navigating their political potential and shortcomings all the more urgent, and the stakes increasingly higher.

It is such contradictions and tensions that are explored within “Resisting Images”. The exhibition brings together a range of works operating at the frayed edges of docu mentary practices, and at the front of the politics of repres entation. As its title suggests, the works in the exhibition address this ambivalence within an imagesaturated present, that is: they look at images both as a means of resistance and as a mode of control to resist against, a unique sort of pharmakon, a poison and a remedy.

Kunstraum Kreuzberg/Bethanien

21st November-17th January 2016

Curated by Marianna Liosi and Boaz Levin

With: Abbas Akhavan, Özlem Altin, Gilad Baram, Bernadette Corporation, Harun Farocki, Massimo Grimaldi, Sharon Hayes, Daniel Herleth, Darius Kazemi, Ken Lum, Martha Rosler, Falke Pisano in collaboration with Archive Books, David Reeb, Sandra Schäfer, Allan Sekula, Peter Snowdon and Ian Wallace

Kunstraum Kreuzberg/Bethanien

21st November-17th January 2016

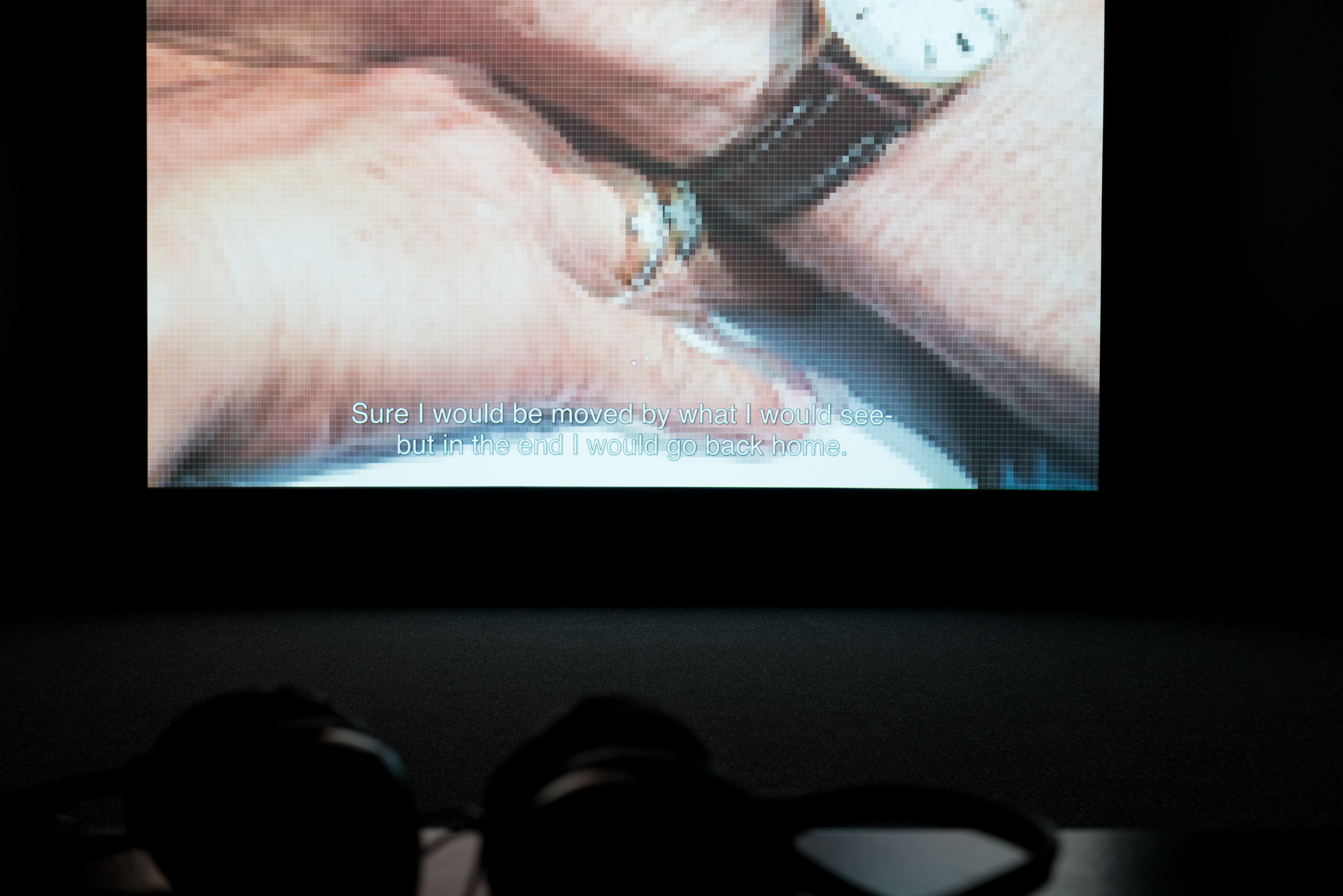

Regarding Spectatorship: Revolt and Distant Observer is an ongoing research project curated by Marianna Liosi and Boaz Levin exploring the notion of mediated political spectatorship.

Regarding Sepctatorship grew out of an initial interest in the social protests that took place during 2011 in Tunisia, Libya and Egypt, commonly referred to as the Arab Spring. As these events unfolded, followed by similarly highly mediated political protest across the globe, an ever growing number of people seemed to be experiencing political unrest from afar. Images of protests were disseminating at exponential speed and breadth. New “social” media as well as more traditional broadcast communication channels contributed to the events and became as much a part of the spectacle as its medium. Photos of graffiti with slogans denouncing the autocratic regimes spread across western media channels. Amongst these slogans were also the names of “social networks” such as Facebook and Twitter. Images of graffiti which read “democracy in Tunisia, thank you Facebook” gained much – some would say disproportional – exposure on international news outlets. Many took this as a sign of technology’s emancipatory potential, going so far as to dub the events the Facebook Revolutions. Many others have criticised the voyeuristic character of what they perceived as couch politics and the futility of so called clicktivisim, as well as the historically deterministic view of techno-utopists.

Whether or not technological innovation played a determining role in the mobilisation of popular protest – circumventing traditional, state-run, top-down, media channels – became a topic of much debate. And yet, the notion of the spectator – all those millions of distant onlookers, to whom these images and reports were channelled – received little attention if any at all.

Thus we chose to start our research from simple introspection – thinking of our possible relation towards these and similar events as spectators, questioning our agency and interest and asking how might we be implicated within this peculiar long-distance relationship. Is mediation inherent to the contemporary political sphere? Is political spectatorship intrinsically voyeuristic, or, conversely does it carry emancipatory potential? Is the act of viewing individual and solipsistic, or does it also affect the collective sphere?

The initial interest in understanding and interrogating the effective role that social media and portable technological devices played in the protests in North Africa gave way to a more general diachronic consideration of the relation between media and politics, spectators and political actors, exploring events such as the war in the Ukraine, the protest in Ferguson and Hong-Kong, as well as the role media played in past events, in El Salvador, Iran and France, to name but a few.

Ever since the early 19th century, in aftermath of the French Revolution, newspapers, pamphlets, posters, telegrams and later, radios, amateur cameras and their contemporary pocket-sized counterparts, smart-phones, have been instrumental to the establishment of political communities and the facilitating of political discourse. Media played an active role in spreading, reporting and relaying protests, at times by empowering, and at others by dis-informing, the public.

As Benedict Anderson has written “print-capitalism (…) made it possible for rapidly growing numbers of people to think about themselves, and to relate themselves to others, in profoundly new ways”. And as many geographers have noted, a fundamental aspect of communication is that it in-forms and recomposes our perception of space and time, thus enabling dispersed communities and individuals to feel they are part of a cohesive body politic, an “imagined community” in the words of Anderson.

Over two hundred years ago Immanuel Kant wrote of the French Revolution, focusing his attention at the historical role played by the distant observers of the revolution, rather then that of the revolutionaries themselves 1. Kant too was but a distant observer, gathering what he knew about the events from newspapers and word of mouth. Similarly, Hegel who memorably stated, “reading the morning newspaper is the realist’s morning prayer” has been shown to have closely followed events of political unrest unfolding thousands of kilometres away in the Island of Haiti 2. Both events had an immense influence upon these thinkers, despite, or perhaps because, the fact that their experience thereof was a mediated one, from a distance, as disinterested spectators as it were.

More recently, Rancière has proposed a valuable critique of the very opposition between viewing and acting, suggesting that emancipation begins “when we understand that the self-evident facts that structure the relations between saying, seeing and doing themselves belong to the structure of domination and subjection”. These oppositions, he writes “define a distribution of the sensible, an a priori distribution of the positions and capacities and incapacities attached to these positions. They are embodied allegories of inequality”. 3 Rather then being a passive condition one needs to transform into activity, spectatoship is, according to Rancière, by definition an intricate labor of association and dissociation, a process of learning and teaching. “Every spectator is already an actor in her story; every actor, every man of action, is the spectator of the same story.” Recognizing the act of viewing as potentially creative and generative of new discourses, Rancière suggests a notion of spectator able to transcend his individuality and to interweave possible future narratives.

The voyeuristic or fetishistic gaze and the power relations it might affirm or conduce are left out of Rancière’s purview, and his proposition falls short of a consideration of the technological conditions of contemporary modes of spectatorship. And yet, spectatorship is hardly a static subject matter, nor a neutral terrain. As Jonathan Crary has shown through his scholarly work, the observing subject “is both the historical product, and the site of certain practices, techniques, institutions, and procedures of subjectification.” 4 In other words, the notion of the observer is very much in flux: a terrain constantly challenged, expanded or transgressed. Following Foucault, we can trace the ways through which certain technologies and power mechanism constitute and administer new forms of subjectivity. For instance, the notion of the observer is further complicated when considered in relation to “social media”. As a user, the spectator is addressed with the pronoun “you”, which insinuates a certain level of personal engagement, of immediacy. As Michele White demonstrates, the Internet is widely perceived as a physical shared and immediate space, encouraging spectators to perceive themselves as embedded within the web5.

By focusing primarily on the observer and his relationship towards both the medium and the political event, we hope to shed some new light on a series of age-old questions.

Regarding Spectatorship thus interweaves a diachronic historical perspective, with sensitivity towards evolving media and communication channels, it explores the notion of spectatorship in the context of a range of specific uprisings and events of political unrest, selected on the basis of their particular relation towards visual technologies. The project and exhibition intend to explore – by way of artistic contributions, cultural artifacts, talks and essays – these diverse, and at times contradictory, views.

Finally, the project’s title, Regarding Spectatorship, refers to the paradox that lies at the heart of such an undertaking: that we, by observing spectatorship, are ourselves implicated as spectators.

Marianna Liosi and Boaz Levin

The project's website gathers together solicited essays and archival material by a wide range of intellectuals, alongside a growing collection of cultural references, videos and archival material. Contributors include Brian Holmes (media theorist, culture critic, activist), Vera Tollman (critic and writer), Quinn Slobodian (historian), Sohrab Mohebbi (curator and writer), Oleksiy Radinsky (writer and filmmaker) and Paolo Caffoni (editor and essayist), Simon Faulkner (art historian), Emanuela De Cecco (art critic, writer and curator), Riccardo Benassi (artist).

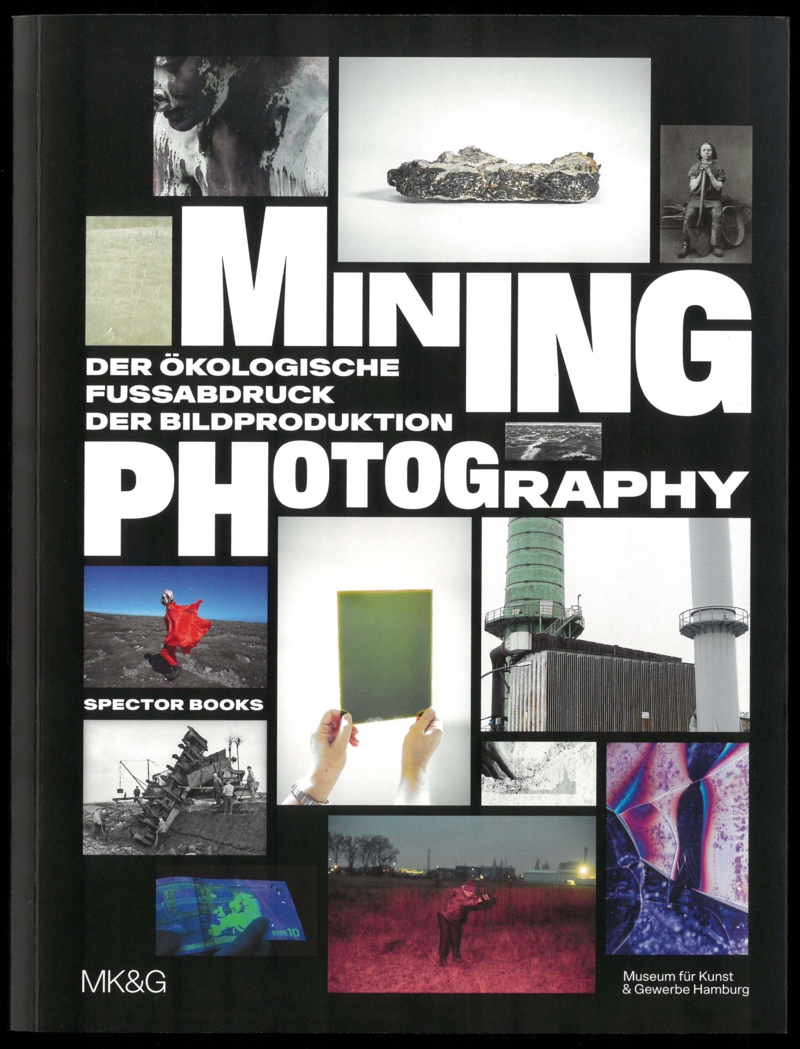

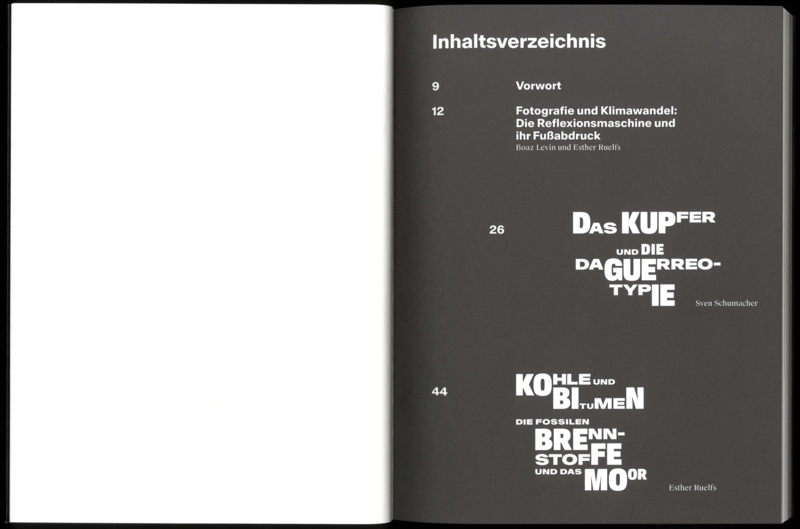

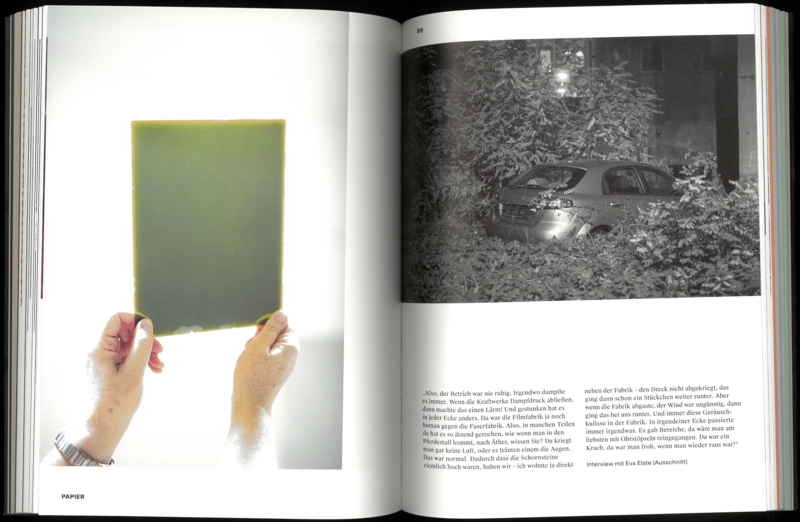

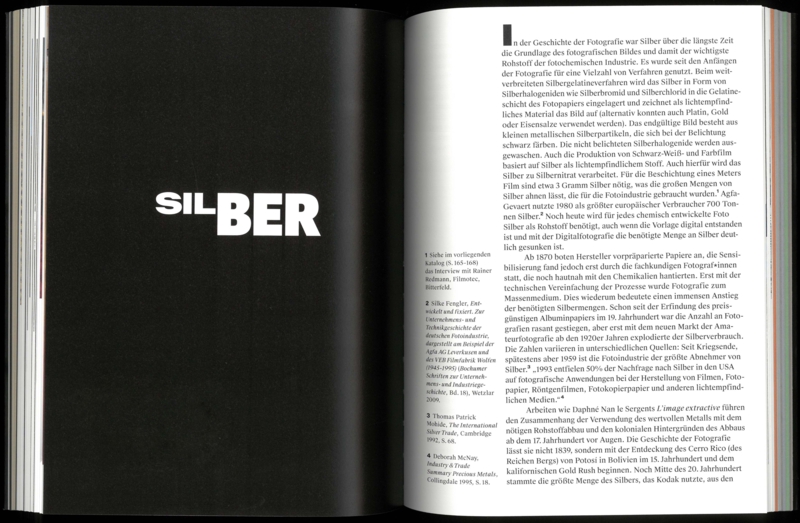

Mining Photography: The Ecological Footprint of Image Production.

MK&G, Hamburg, 2022.

BPA at Gropius Studios

A collaboration between the Gropius Bau and BPA // Berlin program for artists.

Of A Fire on the Moon

Lia Rumma Gallery, Napels

Say Shibboleth | Munich

On Visible and Invisible Borders

Say Shibboleth | Hohenems

On Visible and Invisible Borders

Resisting Images

Biennale für aktuelle Fotografie, Farewell Photography

Regarding Spectatorship

Revolt and Distant Observer

Available here.

Photography has always depended on the extraction and exploitation of so-called natural raw materials. Having started out using copper, coal, silver, and paper—the raw materials of analogue image production in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries—photography now relies, in the age of the smartphone, on rare earths and metals like coltan, cobalt, and europium. The exhibition focuses on the history of key raw materials utilized in photography and establishes a connection between the history of their extraction, their disposal, and climate change. Looking at historical and contemporary works, it tells the story of photography as a history of industrial production and demonstrates that the medium is deeply implicated in human-induced changes to nature. The exhibition shows contemporary works by a range of photographers and artists, including Ignacio Acosta, Lisa Barnard, F&D Cartier, Susanne Kriemann, Mary Mattingly, Daphné Nan Le Sergent, Lisa Rave, Alison Rossiter, Metabolic Studio’s Optics Division, Robert Smithson, Simon Starling, Anaïs Tondeur, James Welling, Noa Yafe and Tobias Zielony, along with historical works by Eduard Christian Arning, Hermann Biow, Oscar and Theodor Hofmeister, Jürgen Friedrich Mahrt, Hermann Reichling, and others, and historical material from the Agfa Foto-Historama in Leverkusen, the Eastman Kodak Archive in Rochester and the FOMU Photo Museum in Antwerp as well as mineral samples collected by Alexander von Humboldt from the collection of the Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin.

Texts: Siobhan Angus, Nadia Bozak, Boaz Levin, Christopher Lützen, Brett Neilson, Christoph Ribbat, Esther Ruelfs, Sven Schumacher, Karen Solie, Julia Wiedenmann

Esther Ruelfs is an art historian and head of the Photography and New Media Collection at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg (MK&G). Boaz Levin is a writer, freelance curator, and co-founder of the Research Center for Proxy Politics.

176 pp.

with 20 black-white and 74 colour illustrations

thread-sewn paperback

Leipzig July, 2022

ISBN: 9783959056328

Edition Number: 1

Width: 19 cm

Length: 25 cm

Designers

Studio Pandan

Editors

Boaz Levin, Esther Ruelfs, Tulga Beyerle

“Judith Kakon’s book Stolen Language can be understood as an exhibition in which her works and working materials are brought into relation and curated anew.”—Simone Neuenschwander

With this book, Judith Kakon (b. 1988) extends her artistic practice by relating her works to her working materials in a nonhierarchical and nonlinear manner. This conceptual approach coincides with the explorations in her artworks, which focus on the reciprocal relationships between society and commerce, and the impact of accelerated economic developments on human interactions with one another and with their environment. Kakon’s working method highlights the ubiquity of commodity circulation and examines selected cultural references via reappropriation of existing forms and modes of production. Stolen Language, published on the occasion of the solo exhibition Judith Kakon. Manor Art Prize Schaffhausen 2021 at the Museum zu Allerheiligen Schaffhausen, is a form of visual research dedicated to often-intangible patterns of exchange and resisting conventional understandings through alternative indexes and perspectives.

Edited by Isabelle Köpfli, Museum zu Allerheiligen Schaffhausen

Texts by Quinn Latimer, Boaz Levin, Simone Neuenschwander, and Sadie Plant

2021

English / German

152 pages

Softcover, 20.5 × 27.5 cm

ISBN 9788867494866

€ 22 / $ 25 / CHF 25

Link to review.

Scholars from a range of disciplines interrogate terms relevant to critical studies of big data, from abuse and aggregate to visualization and vulnerability.

This groundbreaking work offers an interdisciplinary perspective on big data and the archives they accrue, interrogating key terms. Scholars from a range of disciplines analyze concepts relevant to critical studies of big data, arranged glossary style—from abuse and aggregate to visualization and vulnerability. They not only challenge conventional usage of such familiar terms as prediction and objectivity but also introduce such unfamiliar ones as overfitting and copynorm. The contributors include a broad range of leading and agenda-setting scholars, including as N. Katherine Hayles, Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, Johanna Drucker, Lisa Gitelman, Safiya Noble, Sarah T. Roberts and Nicole Starosielski.

Uncertainty is inherent to archival practices; the archive as a site of knowledge is fraught with unknowns, errors, and vulnerabilities that are present, and perhaps even amplified, in big data regimes. Bringing lessons from the study of the archive to bear on big data, the contributors consider the broader implications of big data's large-scale determination of knowledge.

ATLAS PROJECTOS

2020

ISBN 9789895473427

128 pages

Softcover

19 × 12.5 × 1 cm

The third issue in the Next Spring series focuses on one film work, Havarie (2016) by Merle Kröger and Philip Scheffner, which is likewise based on a single image but with many sounds that bring the dynamics of the Mediterranean Sea closer. Titled On Distance, the essay by Berlin-based art writer Boaz Levin is both a response to the film and a reflection on the experience of living at a distance to close relations, from choice or necessity, through mass migration or constant mediation. In a world facing a planetary challenge like no other, it is all the more timely to be reckoning with distance, not as an obstacle for action or an excuse for inaction but to view it as a common condition for thinking through the political.

Next Spring is an occasional series of reviews published in book form. Each issue is an essay of art criticism focused on a work of moving image. Published in English and the language of place.

Laura Preston (ed.)

Published in partnership with Adam Art Gallery Te Pātaka Toi

Available through Anagram Books

Link to article

Review of “Ground Zero” at Schinkel Pavillon, Berlin, TZK 117

Link to issue

This December, Sri Lanka will inaugurate its first museum of “modern and contemporary art” in Colombo, the country’s commercial capital. The opening of the museum comes on the heels of a tense presidential election campaign that brought to power Sri Lanka’s former wartime defense chief, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, often credited for ending the country’s three-decade-long civil war by brutal means: a United Nations report estimates that as many as 40,000 civilians, mostly Tamils, were killed during the last months of that war, with thousands still listed as missing. Rajapaksa has since been accused of war crimes.

In the aftermath of the war, and coinciding with an aggressive push toward market liberalization and rapid economic growth, Sri Lanka quickly became the site of a burgeoning art scene and market. The Colombo Art Biennale was launched by a consortium of galleries just months after the conflict came to its bloody end, with other commercial galleries, an art fair, and now, evidently, a museum all following suit. Why has art become increasingly synonymous with economic liberalization, with art fairs sprouting like mushrooms on the damp earth of economic and social inequality? Grab an itinerary from your next jet-set art-world impresario and you’ll find a list of countries ranking high on “economic freedom” indexes: the UAE, Hong Kong, the UK, Switzerland: all bastions of property rights, an archipelago of low-to-no-tax zones where offshore assets can be safely shelled. These are the kinds of places where capital flight, as historian Quinn Slobodian has recently written, is seen as the most sacred of human rights.1

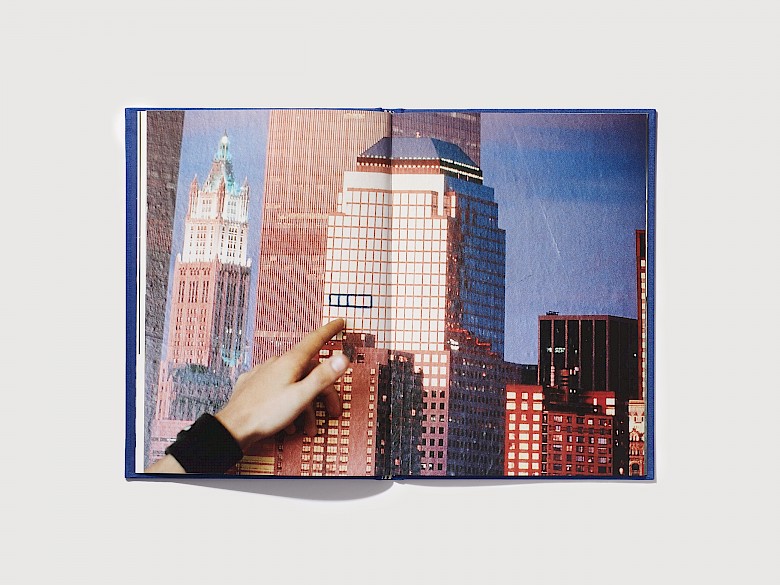

“Ground Zero,” an exhibition by Christopher Kulendran Thomas in collaboration with Annika Kuhlmann at Berlin’s Schinkel Pavillon, offers an ambitious and complex, if at times convoluted, meditation on the relation between the institutionalization of “contemporary art” and the reorganization of the global political economy. The work deftly traces the art boom that swept Sri Lanka in the aftermath of its civil war, questioning contemporary art’s relation to a human rights discourse “used to justify imperial ambitions” and offering a critique of the humanist abstractions it sees as the basis of both.

At the center of the exhibition is a video titled Being Human (2019), projected on a large translucent screen dividing the space. The video follows the character of a young Sri Lankan expat artist (not unlike Christopher), portrayed by Ilavenil Jayapalan, as he returns to the island in the war’s aftermath. There, he discovers his erstwhile homeland of Marxist-separatist Tamil Eelam has been eradicated and replaced, as it were, by a thriving market economy and a globally connected art scene, flush with cash. As we tour the island, Jayapalan talks about AI, Kant, biopolitics, human rights, and posthumanism, in what might as well be the output of a prosumer-grade generative adversarial network (GAN) applied to a decade of e-flux verbiage.

This judgement is not meant as an indictment. The other two characters we encounter during the video are, in fact, synthetic assemblages scraped from the web: “deepfaked” doppelgängers of Taylor Swift and Oscar Murillo. The two are taken as emblematic of our radically malleable, free-floating, networked contemporary; highly mediated products valued, paradoxically, for trafficking in immediacy or even authenticity. Their likeness almost fooled me (with “Murillo,” I found myself failing the Turing test). The soundtrack, too, is a mix of zeitgeist cocktail and readymade, partly lifted from Arthur Jafa’s The White Album and partly based on an algorithmic reverse engineering of Max Martin’s secret sauce behind Swift’s all-time hits. The 25-minute looped video both frames and is framed by a “show within a show” of sculptures and paintings by Sri Lankan artists Upali Ananda and Kingsley Gunatillake, purchased by Thomas from their galleries and restaged here – as if they had stepped out of the video, where they also appear – as readymade-props. For much of the video’s duration they remain hidden, flashing intermittently from behind the frame. It is as if the exhibition in its entirety is wrapped by yet another set of scare quotes, one more semblance in this dizzying hall of mirrors.

Yet for all its novelty, the art world’s fascination with AI in its various guises often ends up rehashing what is, in essence, a well-trodden modernist trope; after all, the generic and clichéd presented as a form of determinism has been with us at least since Flaubert’s Bouvard et Pécuchet, Mal- larme’s Coup de dés, Musil’s Mann ohne Eigenschaften, and, of course, Duchamp. The logic that informed many of these works still seems to be applicable when it comes to the scraping and synthesizing of your latest GAN or bot. At the heart of this trope is a quandary concerning the possibilities for creativity within a context dominated by market logic: questions of authorship and taste in the age of newspapers; mass advertising; “creatives”; target audiences; and, now, networked devices and the data mining they enable. If anything, algorithms have simply furthered this challenge in that – as Wendy Chun has eloquently shown – preferences for less generic and ostensibly more “original” content are paradoxically also easier to predict using social media algorithms. The more one deviates from the mean, the more predictable one becomes.2 As synthetic Swift quips, “Everybody demands authenticity, and every artist believes that they are for real. I mean, I believe that I’m genuine in what I’m doing. But that’s the paradox. Because so does everyone else.”3

So where does this leave Thomas, Kuhlmann, and us? How is one to escape the shapeless, all- devouring blob of the contemporary with its de- sire for synthesized, neatly marketed authenticity? Despite its lamentation about “the contemporary,” “Ground Zero” is itself elaborately timestamped by bleeding-edge tech and trendy posthumanist discourse. But maybe that’s the point? The historical scope of their narrative seems to be its redeeming factor. “This is contemporary art, and nowadays it’s everywhere. But what is it, and how did it get here?” Jayapalan asks at the video’s opening scene. The project of making “here” everywhere is key to this story. Asking about the origin of contemporary art requires that we ask about the origins of the global economy.

A history of globalization, and more specifically the development of neoliberalism, is however conspicuously absent from the exhibiion’s narrative. Instead, Thomas and Kuhlmann trace the origins of their story to the inception of universal human rights, and it is here that their plot veers toward slightly more predictable art-world terrain. Like contemporary art, which Jayapalan (channeling Groys) describes as being governed by a logic of radical equalization – “an art that no longer discriminates between mediums, or disciplines or historical or cultural or geographical refence points” – the notion of international human rights, too, posits a space of “theoretical equality” that is in fact “mediated by unequal powers,” to quote synth-Murillo. So far so good, but the missing link here is neoliberalism. In recent years, numerous critics have noted the twinned birth of human rights and neoliberalism and their parallel historical trajectories, questioning the complicity of a human rights discourse insulated from matters of economic and social justice in a world of radical inequality. Are human rights and neoliberalism identical? It’s a legitimate question, but one which is left unasked. Instead, we are offered a wholesale condemnation of human rights and a vague plea for some sort of posthumanist, decentralized autonomous system of governance that feels like a worn art-world cliché.

Be this as it may, “Ground Zero” remains a complex and ambitious exhibition, joining a rare group of works – including Walid Raad’s Scratching on Things I Could Disavow (2007–2011) and Hito Steyerl’s Is the Museum a Battlefield (2013) – in offering an example of a scaled-up project of Institutional Critique, attempting to address the infrastructure, politics, and ideology of today’s accelerated and globalized means of distribution and display.

Yet if we are to better understand contemporary art, seeing it as a purely homogenizing force is not enough. Contemporary art might tend to the eradication of geographic difference, but it still has a map. A quick look at that itinerary we borrowed from our art-loving one-percenter would show an art circuit plotted along the shores of rising inequality; it accrues not where there is a strong presence of human rights but, rather, where a specific historical understanding of human rights – one that places property rights above all else and is thus central to neoliberal ideology and statecraft – is in place.

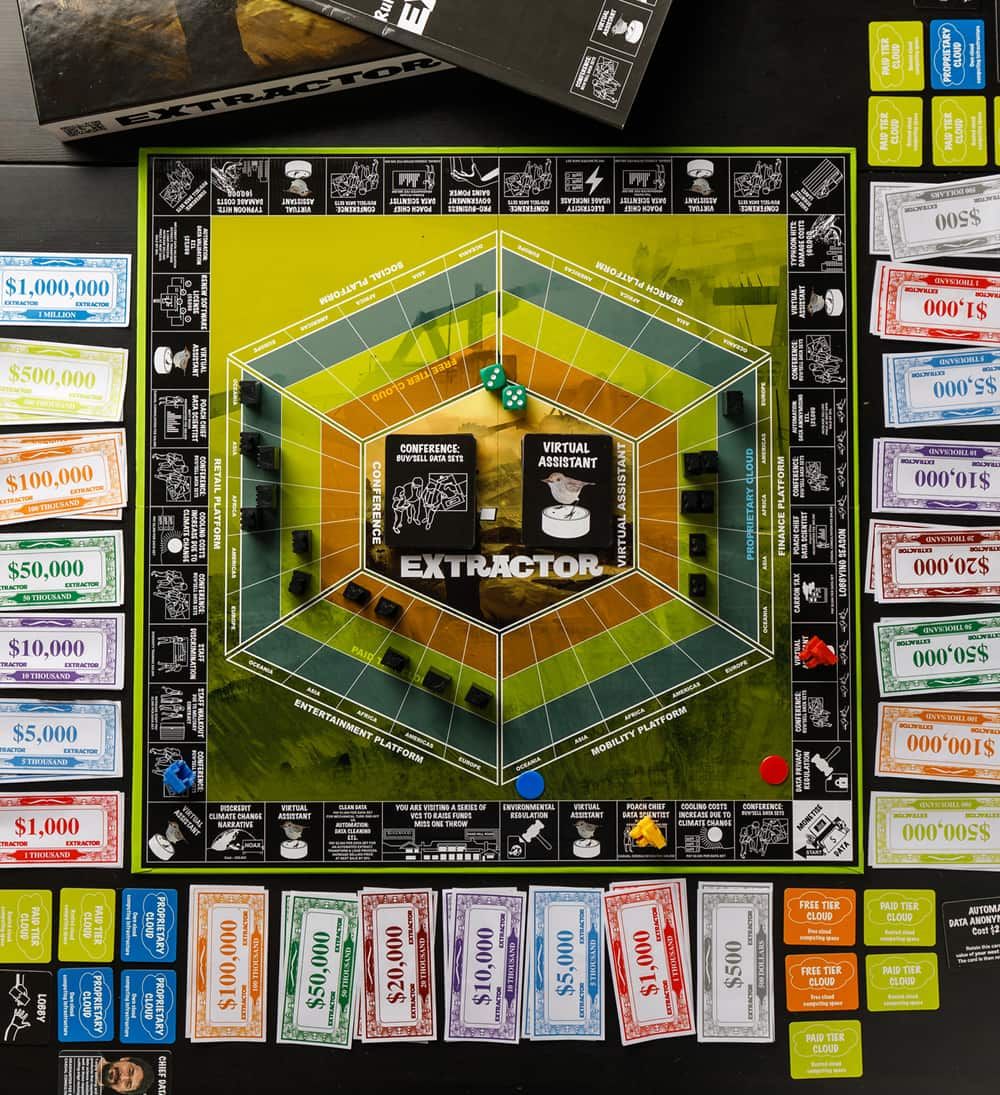

A three-in-one artwork/board game/catalogue about Simon Denny’s exhibition Mine, which takes a look at data and resource mining as a reflection of hope and anxiety about the environment, technology, and work. Read about the art while playing your friends in a competitive scramble for world data domination. (More info about the exhibition here.)

Extractor will turn any tree-hugging humanitarian into a data-wrangling tycoon. It’s the Wild West of data extraction and you’ll need to buy up big if you want to survive.

Includes everything you need to play—game board, dice, data sets etc.—and a rule book featuring essays from Boaz Levin and Vera Tollmann, Tony Birch, Kate Crawford and Vladen Joler, and Tiziana Terranova, and a preface by Mona curators Jarrod Rawlins and Emma Pike.

Link to purchase Extractor

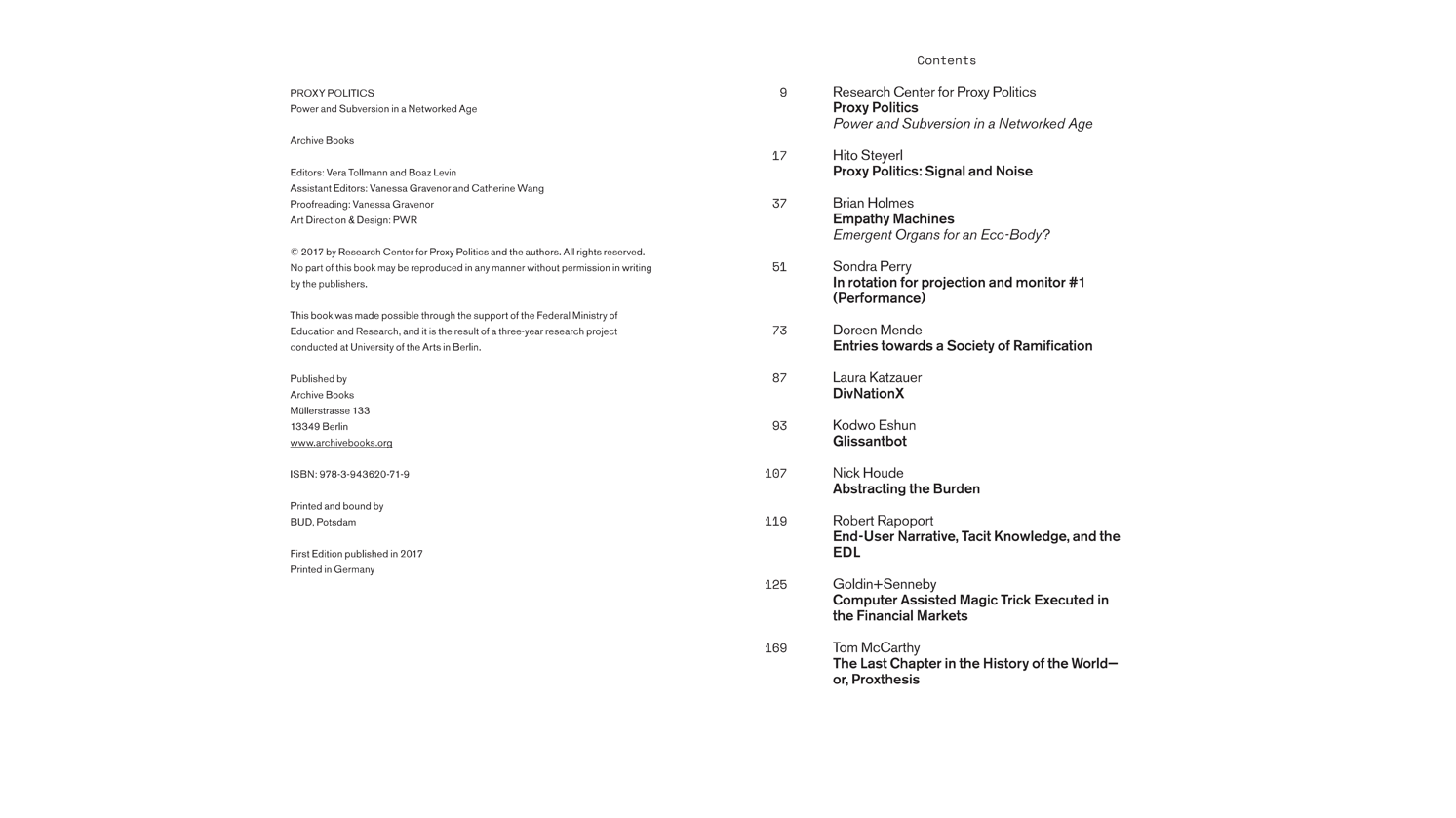

By Boaz Levin and Vera Tollmann

Written for "Extractor", a catalog for Simon Denny's exhibition "Mine", MONA, Australia.

By Boaz Levin and Vera Tollmann

Written for "Extractor", a catalog for Simon Denny's exhibition "Mine", MONA, Australia.

Overture: A Thornbill's Tale

As far as we know, the King Island Brown Thornbill may already be extinct; if not, its extinction is imminent. The likelihood of its permanent disappearance during the next two decades is estimated to be as high as 94%, lending it the dubious honor of leading the grim list of Australian species under threat of extinction1. What do such numbers tell us about the potential for the species’ survival in facing global warming? As we write this, more than fifty bushfires are burning in Tasmania—neighboring the Thornbill’s habitat on King Island—and ravaging 99,000 hectares of land in the past month2. Events of this magnitude are hard to grasp: extreme and alarming, but also abstract and somewhat removed— by proximity, but also comprehension – from our lives. How can we act? These exceptionally large fires were caused by a drought and an extreme heatwave that hit this summer in Australia, a country at the forefront of inconvenient truths.

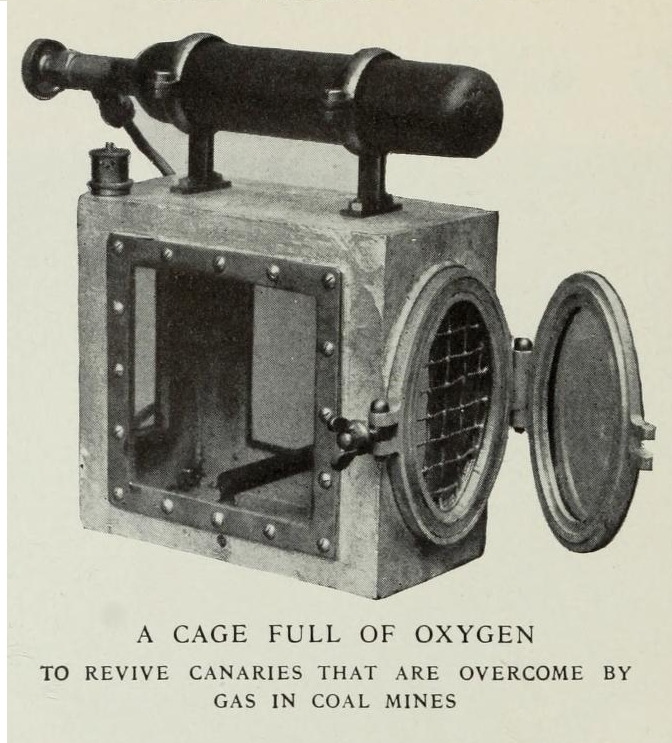

The Thornbill, also called the Acanthiza pusilla archibaldi, is a bird without a lobby. Roughly ten centimetres in length, it is a small fowl with a long thorn-shaped bill (hence its name), a russet forehead with indistinct pale scalloping, red eyes, olive-brown upper parts, a greyish tail marked by a dark band near the end and off-white underparts with dark streaks on its chin, throat and breast. It has been described invariably as ‘unremarkable’ and ‘not sexy’, lacking the ‘marketability’ of other endangered species being sent off as iconic ambassadors onto our touch screens 3. It is, however, a skilled mimic, with a ‘rich, musical warble’ of a call. Adult Thornbills are known to mimic the calls of other species and, sensing approaching danger, they simulate a chorus of different alarm calls 4. Recently the Thornbill seems to have inadvertently emulated the role of another bird: it has been called the 'canary in the coal mine' of the Holocene extinction, the ongoing eradication of species during the current epoch as a result of human activity5. Like canaries employed in coal mines as early warning systems to detect the presence of carbon monoxide, the Thornbill's imminent disappearance is an alert to the deadly effects of carbon emissions on a planetary scale.

The canary’s fate is emblematic of what has been called the Anthropocene, a term used to describe 'humanity’s catastrophic effects on the planet’s physical and biochemical systems'. Or, more specifically, the ‘Capitalocene’—referring to the symbiotic relation between ecological destruction and capitalist expansion, starting from the fifteenth century with seafaring; a term we’ve chosen to use as a framework throughout this essay to describe our current age 6. The canary is a bird, named after an island, named for its dogs: Canariae insulae (‘islands of the dogs’). Being named after what is commonly considered to be the earliest domesticated species will turn into a self-fulfilling prophecy. The canary with which we are familiar today—the proverbial canary, whose tweet, tweet tweet song, gave its name to the mid-nineteenth century verb designating the generic chirp or song of a bird, as well as to Warner Bros ever-evasive ‘Tweety’—is itself a domesticated form of its wild Island-dwelling ancestor. Its domestication is the result of European colonisation and centuries of biotechnological manipulation, meticulous breeding and training. Its ancestor: Serinus canaria, the wild or Atlantic Canary, is a yellow-green small perching bird, part of the finch family, distinguishable for the male’s crystalline song. Its ‘discovery’ in the early fifteenth century by European colonists, who were enamored by its call and vivid colors, coincided with the beginning of the European world-economy, and led to it being imported to Europe in large numbers 7. The Canary Islands, known by the Romans as ‘the fortunate isles’ for their fertile volcanic soil and moderate weather, would become ‘laboratories for a new kind of European imperialism’. The Guanches, their native population, were the first people to suffer the fatal consequences of imperialist expansion 8). The bird’s import to Europe also signaled the dawn of the epoch-making ‘Columbian exchange’, as Old World diseases, animals, and crops flowed into the Americas, and New World crops, such as potatoes and maize, flowed into the Old World with the advent of European imperialism 9. It was the beginning of a capitalist world-ecology—the joining of ‘power, nature, and accumulation in a dialectical and unstable unity’—marking the emergence of the Capitalocene 10.

Canaries were presented by explorers as gifts to the court of Castille, and soon to the rulers of France. From there, the birds were exchanged and bred among nobility, with women said to have carried them as accessories perched on their fingers. The following centuries saw a dramatic increase in the fowl’s import to Europe, and by the nineteenth century there was something of a canary craze in Britain and Germany, with its breeding becoming prevalent predominantly among the working class. The bird became a source of supplementary income in times of economic stress, or as one author put it, a hobby which combines both ‘profit and pleasure’11. By the late nineteenth century, the international canary-market was booming 12. While the export enterprise relied on training birds to sing and entertain people in their private homes, the network of trade routes could be described as a ‘hybrid geography interweaving people, organisms, and machines’ 13. Following experiments conducted in the 1890s by Scottish physiologist John Scott Haldane, mines started stationing canaries in their safety lamp cabin, from where they were taken underground to perform as sentinel animals. By the 1920s The US Bureau of Mines regularly employed canaries on their safety and rescue teams, with the ‘hero-birds’ of the Division of Mine Safety Cars considered ‘among the most important employees of the bureau’14. Besides being small and light, and therefore portable, canaries have a high basal metabolic rate, which means they exhibit symptoms of poisoning before gas levels become critical for humans. As the Sacramento Union newspaper reported, ‘in the presence of small amounts of carbon monoxide [the canary] gasps visibly, ruffles up its wings, flutters, and, if sufficient of the deadly gases are present, quickly drops from its perch unconscious and seemingly lifeless’. This deadly use of canaries would continue late into the twentieth century, ending in the UK in 1986, when they were replaced by automatic detectors.

Thus the canary—a bird named after the domesticated canine, which spread with the rise of the European war-capitalism, bred to achieve perfect color and pitch, through speculative cycles of boom and bust, and eventually employed in the toxic catacombs of fossil fuel extraction—sings the song of the Capitalocene. And now, the King Island Thornbill joins its chorus.

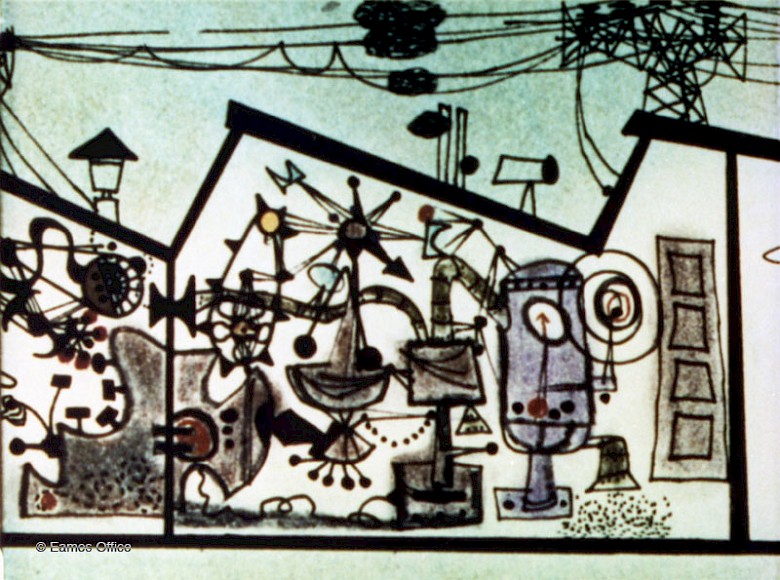

Mines and Clouds

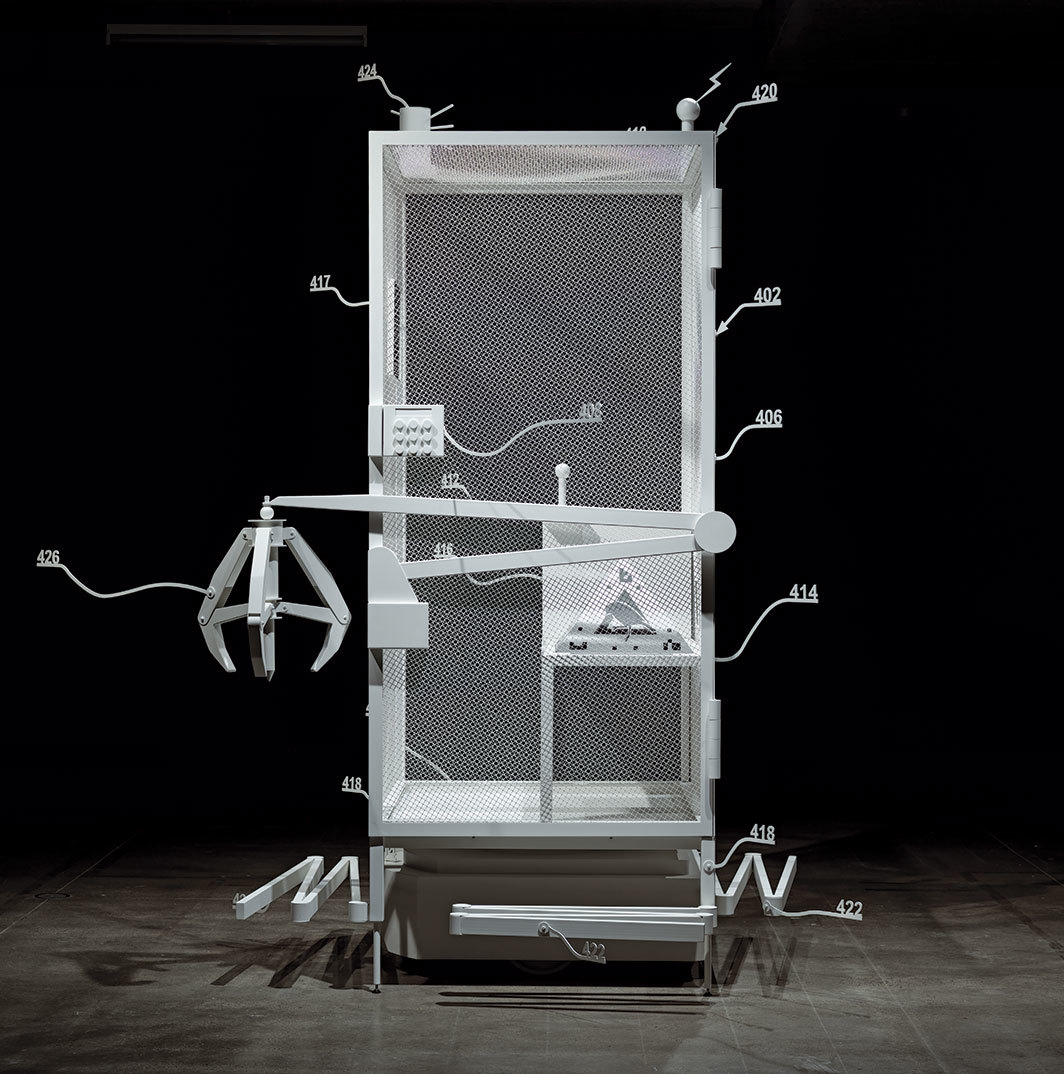

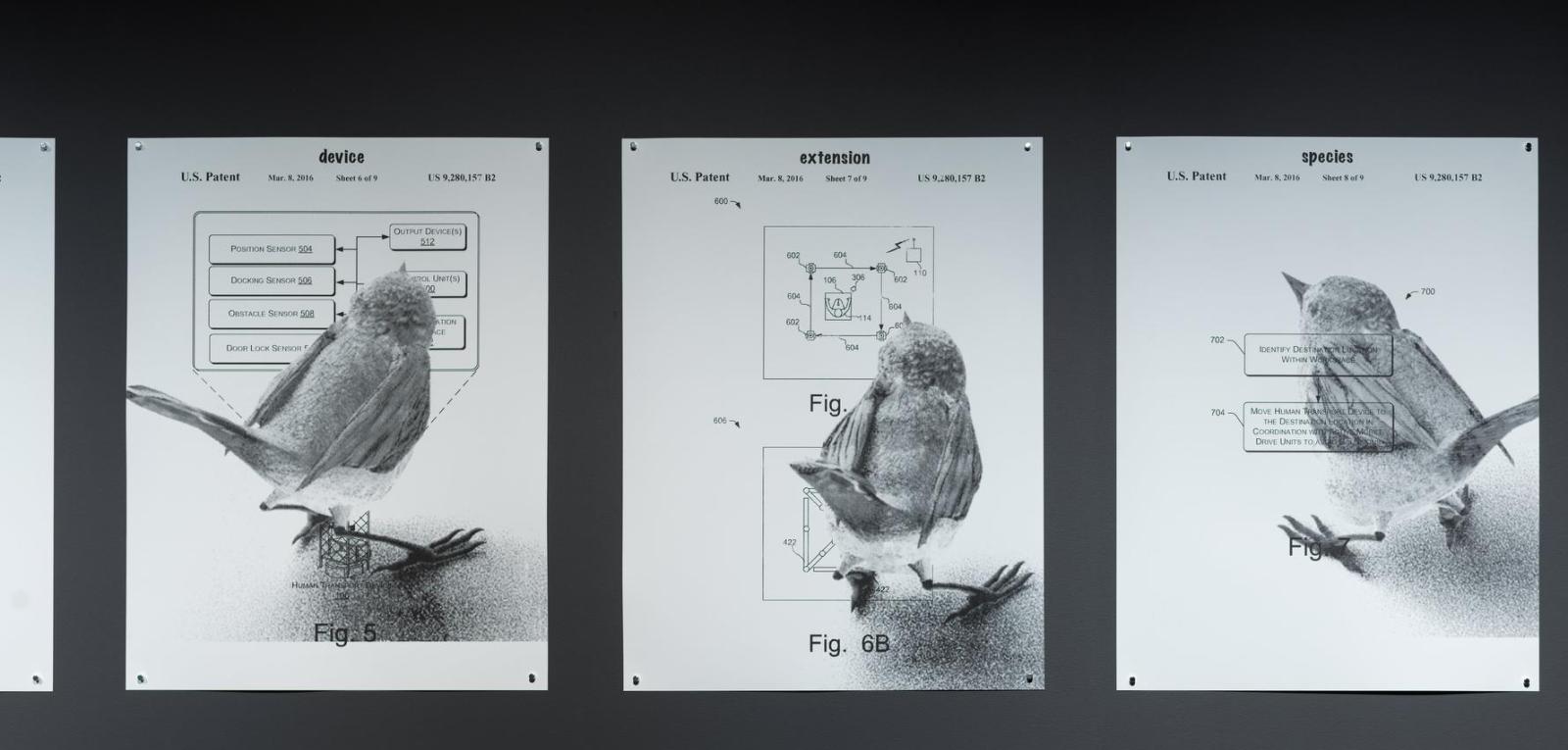

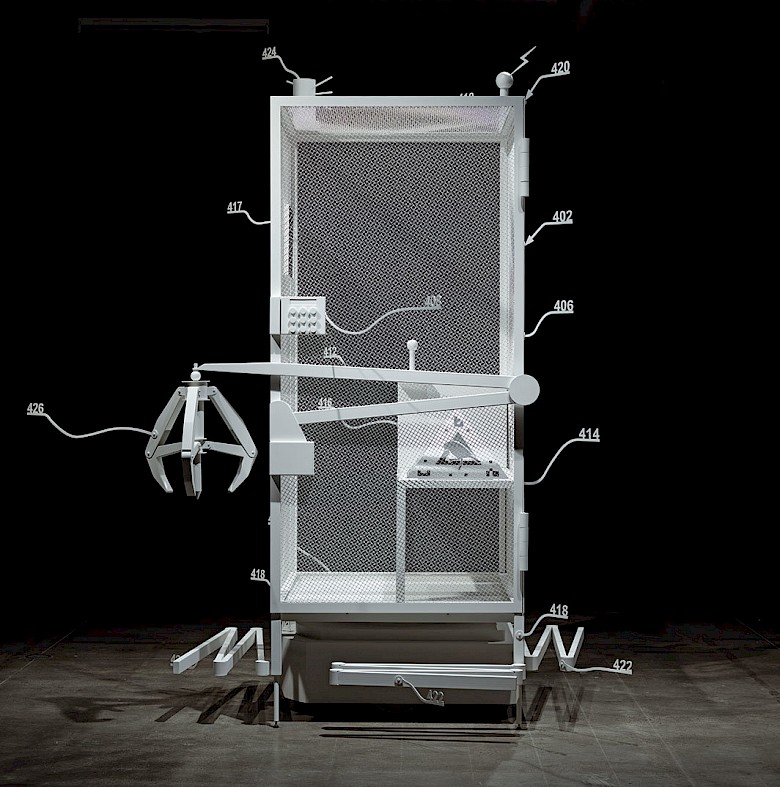

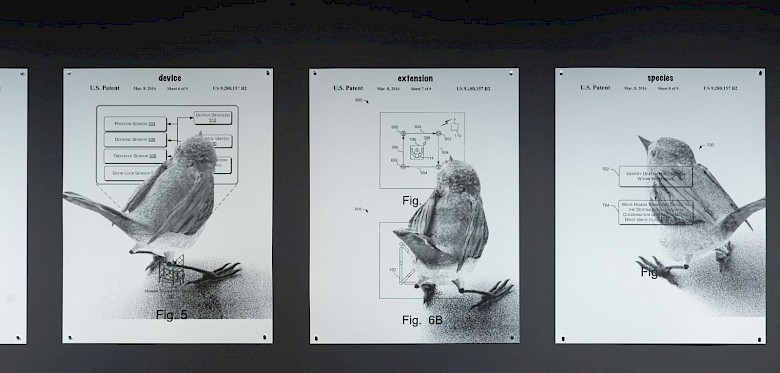

A Thornbill in a canary cage is the first thing one encounters upon entering Mine, Simon Denny’s solo exhibition at the Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) in Tasmania. More accurately, one encounters an empty cage—fully equipped and meticulously configured to host a living canary—and in it appears a fluttering life-size animation of the endangered bird. This bird is only visible through the ‘O’, Mona’s digital curatorial device (hosted by a provided iPod or an app on the user’s own iPhone).The O is filled with information selected and designed by the artist, turning the show into a carefully choreographed double space—both physical and virtual—of objects and augmented reality. A clawed mechanical arm is attached to the cage, and various graphic elements, notation and labels protrude from it.When looking through the O, different infographics pop up on the screen. The cage, we learn, is a life-sized 3D reproduction of an image taken from a patent filed by Amazon, invented and designed to house human warehouse workers interacting with heavy machinery—an uncanny illustration of a dystopian future for the interface between worker and machine. Tweets relating to contested mining operations in Australia run across the screen. The virtual presence of this additional layer turns the objects in the exhibition space into interfaces and the museum into a platform. As we shall explain in this essay, the Thornbill in a canary cage becomes a tangible way of perceiving the radically intangible logic of extraction on a planetary scale.

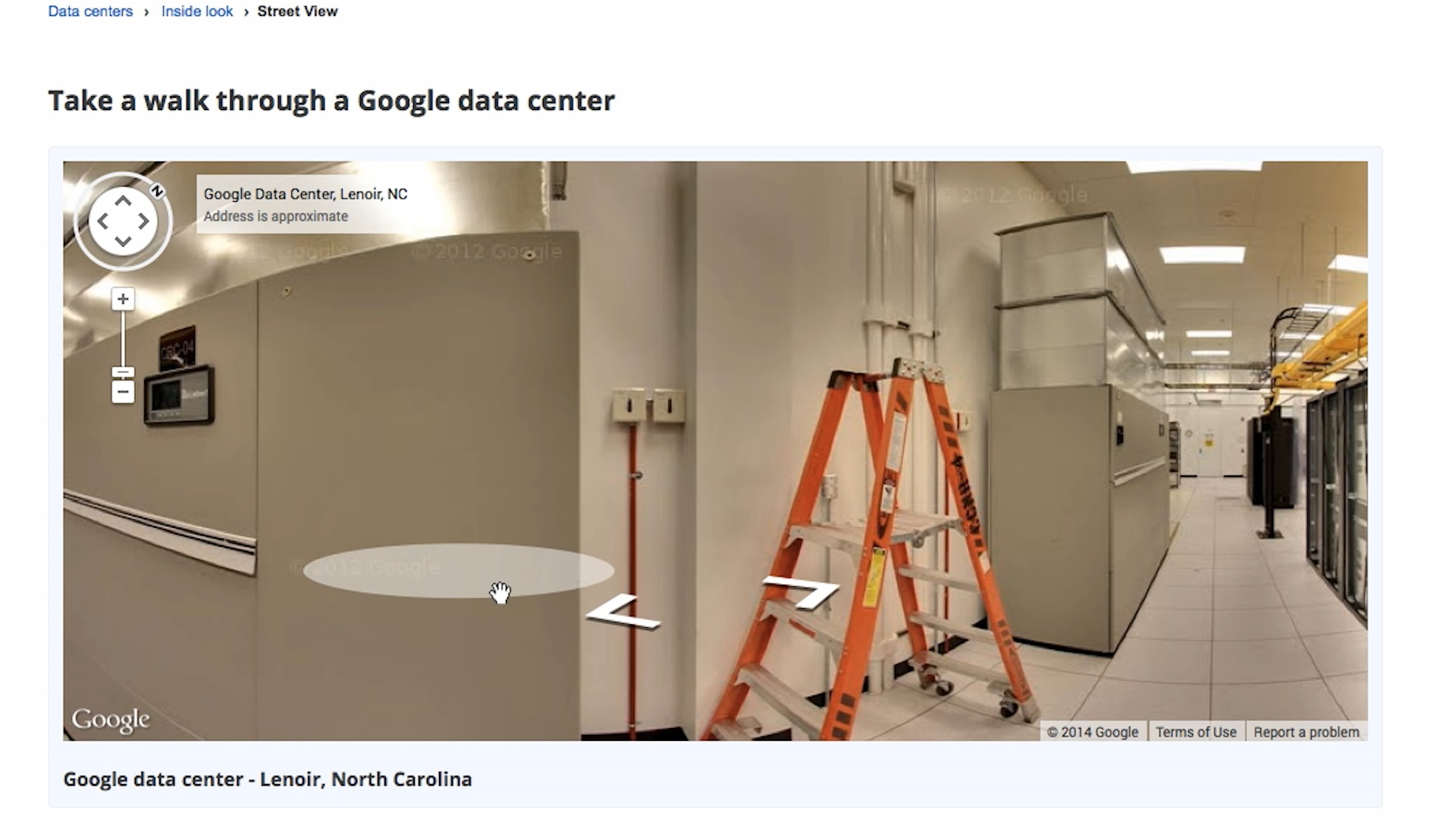

The exhibition is introduced with a research diagram created by Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler titled ‘Anatomy of an AI System’, created to accompany an essay by the same name (both featured in this volume). The wall-sized map outlines the entire process of producing Amazon’s AI-powered voice assistant Echo Dot, an inconspicuous cylinder-shaped ‘smart’ home appliance. In dizzying detail, Crawford and Joler chart the data, labour and resources used for its production, maintenance, distribution and use: from rare earth mines, through to an array of labour processes and global supply chains, and, finally, to people’s homes, and simultaneously to the immense and ubiquitous data centres of the so-called ‘cloud’. Their diagram introduces the central challenge addressed by the exhibition, that of thinking and representing labour, resources, and extraction together, rather than as disparate and unrelated processes in a vast and intricate global economy.

Where Crawford and Joler disassemble the black box, Denny unearths a composite vision of our dystopian present through the image of the mine: mines for the extraction of valuable minerals or other geological materials, and data mines, where human action is surveilled, aggregated, processed, and ultimately monetised—literal mines and metaphorical mines. The building site of the Museum of Old and New Art adds to the mining metaphor: the museum is carved into the rock of the Berriedale peninsula, the exposed sandstone cliffs towering over you as you descend into the labyrinthine exhibition galleries.

The rise of so called ‘data-mining’ comes with the proliferation of mobile communication devices and ‘social media’, as well as the centralisation process described euphemistically as ‘cloud’ computing. Here, the metaphor of ‘mining’ becomes a brilliantly succinct way of naturalising data, conveying the notion that data (as its etymology suggests) is a resource to be tapped into and extracted with the help of mechanical ingenuity and business acumen, as if it were a precious ore or fossil fuel. Expelled from the realm of either propertied cultural relations or productive labor to that of a virginal terra nullius, data is the ‘new oil’ 15, meaning metaphors of harvesting or mining demonstrate how ‘deep’ avatars or other data gathering scripts dig into the data pool that is social media.

This nexus of extractive processes, both literal and metaphorical, has led a growing number of scholars to identify an expanded notion of ‘extractivism as a dominant logic within contemporary capitalism, doomed to expand’16. Understood metaphorically, extractivism refers to the contextual resonance and effects of extractive activities in the economical, political and social fields, such as the surveillance, analysis and monetisation of behavioural data, whereas in a literal sense it describes ‘historical and contemporary processes of forced removal of raw materials and life forms from the earth’s surface, depths, and biosphere’ 17. This expanded understanding of extraction highlights the central role played by ‘capital’s multiple outsides’18, and the continuity of what Marx called primitive accumulation in the present. Similarly, writing at the turn of the century and at the height of imperialist expansion, political theorist Rosa Luxemburg observed that an exchange between capitalist and non-capitalist environments is essential for the existence of the capitalist economy 19. For Luxemburg, expansion has become the true ‘economic condition of existence for the individual capitalist’, a coercive law predicated on the ‘cheapness of commodities’, the capitalist’s ‘most important weapon ( . . . ) in his struggle for a place in the market’. Extraction and expansion are intricately linked. This explains the significance of the frontier for capitalist expansion, as journalist and activist Raj Patel and environmental historian Jason W. Moore have written, ‘capitalism not only has frontiers; it exists only through frontiers, expanding from one place to the next’20. Capitalism needs to invent frontiers that it can overcome, colonise, a ‘nature’—human, or otherwise—that it can ‘cultivate’, put to work, exhaust, and do so as cheaply as possible 21. The frontier ‘concerns how the “outside” is produced, exploited, and policed’, it is a site of ‘perpetual reinscription’, writes critic and curator Vivian Ziherl; a thought which is also inherent to Denny’s amalgam of terrestrial and virtual mining and markets. She discusses the ‘persistent presence of the frontier within the globalizing era’, exploring its traces and reverberations through the visual arts in the context of aboriginal Australia 22. As specific to the Australian case, Ziherl points out the violent ‘de-registration of sacred sites’ by law to extract monetary value from the culturally and religiously sacred lands 23.

There is a strong relation between forced and unwaged labor and extraction, which always strives to maximize value and minimize compensation. And in its expanded sense, extraction ‘involves not only the appropriation and expropriation of natural resources but also, and in ever more pronounced ways, processes that cut through patterns of human cooperation and social activity24. One could think of this as the frontier reaching the human body (and agency).

Australia is home to one of the world's largest mining industries, and is now pioneering in its mining digitisation and automation. It is the primary global exporter of coal and opal, and is second only to China in rare earth mining zinc, gold and iron, making mining the largest sector of its economy25. The rapid expansion of its pastoral and mining industries since the mid-nineteenth century supports Patel and Moore’s assertion that such capitalist expansion exists through frontiers. It was the doctrine of Australia as terra nullius (‘land belonging to no‑one’), established with European colonisation and only formally abolished in the Native Title Act of 1993, that enabled its extractive industries to develop on such an unwieldy scale 26.

In the second room, Denny has installed near life-size cardboard reproductions of automated mining machines in a chimera of a half-built trade fair, showcasing technologies currently in use in Australia 27. Visitors encounter a looming present instead of a daunting future. The cardboard cut-outs are illustrated in a sort of computer-game-like aesthetic and appear heavily used, almost derelict, with traces of machine oil and dirt lending the entire set-up the sort of cyberpunk, worn out, archaic futurity of a post-industrial dystopia.

The sculptures sit on a wall-to-wall board-game layout taken from ‘Squatter’, a popular Australian monopoly-like game in which players run sheep stations as competitive business ventures in the Australian colonial frontier. For the exhibition, Denny created an adapted version of the game titled ‘Extractor’. This new version models and parodies the mechanics of platform technologies and data-extraction businesses, and incorporates different motifs from the exhibition such as the Thornbill. Extractor uses the blatant colonial ideology implicit in Squatter to highlight the expansionist logic essential to data mining, and its digital frontier. A large-scale version of the game occupies the centre of the exhibition space, while boxed playable versions populate the cardboard mining sculptures which double as shelving units. Purchasable, the sculptures are gradually emptied from boxes, only to remain in their skeletal, cut-out form. Denny assimilates to commercial strategies; he embraces the established and recognisable tricks of the trade, developing them to a degree of perfection with the decisive difference that he in fact sells a trigger for reflection of current day capitalism, a theme park for extraction. Since the days of Squatter, pastoral industries have expanded beyond recognition. But agriculture, writes Timothy Morton, ‘is a major contributor to global warming, not just because of flatulent cows, but because of the enormous technical machinery that goes into creating the agricultural stage set, the world’. As such, every game creates a world and utilises a world-picture: in the case of Extractor it is the violent, power consuming, networked world of data mining. Both worlds meet in their imagined frontiers, and in their contributions to the excessive release of carbon into the atmosphere.

In the realm of data extraction, there is a strong development towards ‘the pervasive penetration of extraction into spheres of human activity’ 28. The problems that arise thereafter are manifold, as ‘[D]ata mining reconfigures property relations, working the boundaries of “privacy” while also testing and exploiting the differences, frictions, and connections between heterogeneous jurisdictions’29. These jurisdictions come into the focus of insurance companies, among other stakeholders, while we write. For example, an insurance company demands a third party take care of data gathered with self-driving cars to make sure the data is not manipulated in a particular party’s interest in case of an accident.

The ‘extractive turn’—marking the heavy use of large machinery in formerly human-scale production areas for the extraction of ‘huge volumes of natural resources, which are not at all or only very partially processed and are mainly for export’30—has its effects on logistics, like the need for more cargo transportation and power consumption. And, in turn, large transport infrastructures make way for large-scale production and extraction, such as the Chinese One Belt, One Road plan and the Grand Nicaragua Canal project. Once one sector is scaling up, the connected industries are forced to follow suit. If there is any consolation to be found in this vision of extractivism, it is in the fact that despite capital’s totalising tendencies, its ‘constitutive relation with its outsides punctures and troubles this very process of totalisation’31.

Mine essentially deals with the challenge of representing global extraction processes, and changes relating simultaneously to labour, resources (for lack of a better word), and data (for lack of a better word), without privileging any one aspect. In order to mediate those mostly invisible, large-scale processes and to address what’s at stake, Simon Denny chose to unfold his arguments and concerns though a series of emblematic vignettes and an array of objects, artifacts and corporate brands. The exhibition appears to zoom in and out, in order to straddle multiple scales simultaneously—highlighting local concrete business practices while mapping a global logistics network and supply chain, for example. Visitors interact with the ‘theme park’, a tongue-in-cheek description by the artist, of carefully chosen attractions—intangible objects in real life—from a first-person-screen perspective (familiarised by ‘smart-phones’ and tablets). The show sends a warning signal, like that of the canary bird, whose history we traced in the beginning of this text.

Zooming into the history of mining in modern times, certain categories in the Anthropocene discourse stand out. Aerial pictures reveal the irreversible changes of the earth’s surface, so-called ‘sacrifice zones’. Before the Anthropocene and related ecological problems were virulent, most significantly, living and working conditions mattered. In 1956, the architect Erwin Anton Gutkind described mining towns as an inhuman blending of work and living, which demonstrate the modernist relationship between man, labor and nature32. Gutkind calls it an ‘I-it relationship’ 33. The post-war years were a time of a universal, Western one-world approach: ‘the whole world is our unit of thinking and acting’34. When Gutkind was studying the industry and its damage to the surface of the Earth, he used aerial photographs to make his assessment. The visual material made him stress the ‘rigid layout and the unity by representation’—a modernist ideal and ideology of functionality through abstraction. The aerial perspective went well with a modern rationalised take on earth and its resources, and Gutkind and his fellow editors claimed that the most striking symbol of a new (universal) scale was the airplane, as pioneering artists, architects and theorists had already stated in the 1920s. But Gutkind added a skeptical tone to his analysis, writing that ‘the dumps are the most conspicuous landmarks of the exploitation of the natural resources and of the exploitation of the human “material”’35. With the current process of automatising mining, on the contrary, distances between workers and the site of the mine are redefined, leaving a virtual, abstracted impression, no imprint, impossible to frame in an aerial photograph.

On the other hand, looking into long-term problems caused by mines which are evident after closure, one comes across analyses regarding its toxic (wastewater) remains. Even though the contemporary mining industry tries hard to manufacture a ‘clean’ image—for example mining as envisioned by high-tech companies—the extraction business leaves behind these so-called ‘sacrifice areas’36. Researchers in natural sciences as early as the 1970s, a peak period of environmentalist thinking in the twentieth century, point out the drastic man-made damage: ‘as of 1977, when stricter regulations were implemented, the mining industry alone had disturbed 2.3 Mha in the United States, an area roughly the size of the state of Vermont'37.

It seems so contradictory, disproportionate and mind-bending to think of mining, likely the heaviest and most rudimentarily physical of all industries, as equipped with—and even partly run by—silent computer systems, remote-controlled sensors and data analytics, which are watched over by autonomous drones. The grubby and monstrous business of mining has been gradually integrated into an algorithmic regime. The face of twenty-first century mining is a roll-call of multinational companies like the Swiss technology firm ABB38 Cisco or Accenture, who, in their video ads, represent the industry through images of high-tech command and control rooms for the so-called ‘connected mine’ or ‘digital mine’, which means selling digital tools intended for increased productivity in extractive operations. The company is promoting an extensive, hyper-clean smart system, including live interfaces, video phone feature and VR headsets39. Human operators supervise the operation through an interface of screens, tablets and computers to interact with a digital model of an underground mine as well as an open pit. In their downtown remote control centre40—a glance out of the window reveals a complex of highrise buildings—the digital copy of the mine shrinks into a clear and manageable room size. While the control room can be installed nowhere in particular, the mine needs to be located somewhere natural resources are to be found. If previously an architecture model would serve the task of representation and mediation, in the video it is promoted as a data display and cue for action. Underground, workers data is gathered by a device such as the Caterpillar ‘Smartband’. According to the manufacturer’s advertising, the ‘wrist-worn device automatically detects an employee’s sleep and wake periods and converts data into an effectiveness score, viewable by the employee at any time with the push of a button. If a score is approaching 70%, the employee is considered to be “fatigue impaired”’. Caterpillar claims that workers are being empowered to ‘manage their own fatigue’ and mining companies are enabled to ‘model and predict worker fatigue risk’. The smartband is, they seem to claim, the new canary. But it is also another mine, surveilling and aggregating behavioural data from the mine’s workers, as if it were just another ore. Digitisation has come full circle. The oldest, perhaps most archaic, industry goes digital, and is uploaded to the cloud. Big machines are steered based on micro-technology. Silicon Valley has found a new frontier41.

But let’s zoom out even further to understand what the discourse on mining, extractivism and data tells us in regards to the times we live in. How to grasp its new scale and dimension? Is it possible to represent processes so abstract, so large and all-encompassing, so sticky and messy and global, without falling to abstractions, to generalisations, without losing oneself to detail and seeing the trees rather than the forest?

Scalar dilemmas

A number of theorists from different disciplines have tried to find adequate strategies to deal with the challenge of representing such vastly distributed phenomena. In her book Climate in Motion, historian Deborah Coen refers to climate science as a process of scaling, of ‘mediating between different systems of measurement, formal and informal, designed to apply to different slices of the phenomenal world, in order to arrive at a common standard of proportionality’42. To grasp the human influence on climate change and its future trajectory, it is necessary to zoom in and out, to shift, jump and cut from micro to macro, from the molecular to the planetary, and from the Pleistocene to an imminent future. Timothy Morton calls those things ‘that are massively distributed in time and space relative to humans’ ‘hyperobjects’. This concept reflects his attempt at addressing ‘scalar dilemmas’ by bringing global warming down to earth and relating to it: ‘[T]he time of hyperobjects is the time during which we discover ourselves on the inside of some big objects (bigger than us, that is): Earth, global warming, evolution. Again, that’s what the eco in ecology originally means: oikos, home.’43 Thinking with Morton’s hyperobjects helps increase our awareness of processes generally invisible to us, to create a ‘sense of intimacy’ for climate signs, the sensual footprints of hyperobjects, that speak to us; instead of spreading a message that planet Earth is doomed, Morton wants to ‘awaken us from the dream that the world is about to end’44. Another strategy to represent globally and temporarily distributed extractive processes during the Anthropocene is offered by historian Gabrielle Hecht. In an essay on uranium mining in Gabon and planetary nuclear politics, she describes uranium-bearing rocks as ‘interscalar vehicles’, ‘riding them from Gabon to France to Japan, from the 1970s to our planet’s early history to the distant future’. Her intention is to narrate the different political layers involved in local, national and international business and politics, ‘to understand the Anthropocene and its critiques as scalar projects. This requires treating scale reflexively, as both an analytic category and a political claim’45.

A similar scalar dilemma has long vexed critics of political economy. The difficulty of representing, or mapping, the intricacies of global capitalism in its multiple scales is the subject of Jeff Kinkle and Alberto Toscano’s Cartographies of the Absolute, which asks for an aesthetic of cognitive mapping, as a response to a state of ‘cognitive dissonance’: a sense of disorientation facing an omnivorous capitalist world-system. What is lacking, they note, is ‘a practice of orientation that would be able to connect the abstractions of capital to the sense-data of everyday perception’, and that this is ‘identified as an impediment to any socialist project’46. But maybe scalability and an expansive view are part of the problem, rather than a solution to it? In her essay ‘On Nonscalability’, anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing analyses capitalism’s logic of scaling and expansion: ‘projects that could expand through scalability were the poster children of modernisation and development’ she writes, ‘we learned to know the modern by its ability to scale up. Scalable expansion reduced a once surrounding ocean of diversity into a few remaining puddles. Project advocates thought that they had grasped the world. But they have been confronted with two problems: first, expandability has gotten out of control. Second, scalability has left ruins in its wake’47. Since extractivism and its imperative of limitless expansion leaves behind a ‘damaged planet’, Tsing advocates for alternatives outside scalability logics in favour of biological and cultural diversity.

Novelist Amitav Ghosh has recently addressed similar questions concerning the absence of climate change in works of literary fiction, and specifically the modern novel, and the challenges posed in addressing such issues within an artform so closely related to the development of bourgeois subjects, and to modernity. With the novel, nature is relegated to a role in the background, and the human—preferably individual—psyche, comes to the fore. For Ghosh, climate’s imagery is resistant to literary representation too: ‘[G]lobal warming’s resistance to the arts begins deep underground, in the recesses where organic matter undergoes the transformations that make it possible for us to devour the sun’s energy in fossilised forms’. These substances—coal, petroleum, gas—are ‘viscous, foul-smelling, repellent to all the senses’, or otherwise, odorless and toxic 48.

Beyond the Capitalocene

Contemporary extractivism—from oil, to rare earth, to data—is characterised by a different materiality to that of earlier mining, more often abstract and predominantly automated. But is it true that, as Ghosh writes, for the arts ‘oil is inscrutable in a way that coal never was’? And if so, isn’t data —and its primary existence as numbers in spreadsheets—all the more inscrutable? Or, perhaps, as Denny appears to claim, the problem lays less in the inscrutability of one substance or another, but rather, in the sleight-of-hand of industry and the mostly invisible operations of the entire logistical cycle, and the way both labour and the environment are obscured by it: from rare earth mines to seemingly innocuous hand-held machines and their omnivorous collection of behavioural data, and the absorbing of this data into ‘cloud storage’. The only representation we have of such processes are stock images, blinking server farms, ‘smart machines’ or automated mines seen from drone view. The challenge is to think about labour, resources, and data together. In narrative terms, the difficulty posed is that of breaking away from sequence, into a sort of expanded and spatialised montage, but also of allowing for the viewers identification nonetheless through AR interactivity, offering multiple nodes of entry. Denny’s reference to gaming as a narrative form and organising logic, and as a way by which behaviour is often mined and monetised, addresses similar questions concerning the possibility of representing a highly distributed ‘story’. Games are by definition goal oriented, predominantly governed by a zero-sum, winner-takes-all market logic, relying on the positing of a rational self-interested subject, but they are also about role playing, immersion and identification, and action rather than representation. Players are more than just spectators, for one, they are always implicated, and expected to take action. In this sense games are great tools for modeling and testing future scenarios. Superimposing Extractor on top of Squatter shows how current extractive industries are built upon a long history of expropriation, while the game’s dizzyingly steep narrative—profitability increasing exponentially the further one progresses, making radical inequality a feature, rather than a bug—corresponds to the mechanics of the data industry, and by extension to extractive capitalism.

What could be an alternative to this sort of extractivist logic? Are there examples of critical uses of datafication that could be harnessed for alternative ends, or even to prevent the future ascribed to us currently with statistical near-certainty? Can the miner outsmart his smartband? Climate-change research is one possible example of a critical use of predictive data modeling. Such models make predictions based on past correlations, not in order to affirm the status-quo—to mine past behavioural patterns and monetise future actions—but rather, in the hope that they will prompt us to act differently and create new futures49. These are predictions made with the hope that they fail.

To return to our Thornbill, we can only hope that the grim prediction of its coming extinction fails —that the warning succeeds and the Thornbill comes to thrive again. Meanwhile, a community effort is underway in order to gather more data about it, where ‘experts in conservation management, specialist bird researchers, dedicated birders, and passionate local landholders all give their time freely to monitor endangered species’50. The bird’s most recent sighting, in 2016, was documented as part of the 'Wing on King' bird monitoring project. This is not a case of government outsourcing, or unwaged labour extracted via platforms, but rather ‘unpaid work by dedicated Australians stepping up’51. They do so, not out of desire to colonise yet another ‘outside’52, to conquer another frontier, but with the hope that a persistent, collaborative grassroots effort will demonstrate, if only provisionally, that despite capital’s totalising tendencies, another world, with another future—beyond the Capitalocene—is possible.

First published on Contemporary Hum

First published on Contemporary Hum

Last week it was warm once again in Berlin. The sky was a hue of brilliant blue and people filled the cities’ parks, basking in the soft warmth of a rare mid-winter sun. It’s only February, but it feels like spring is just around the corner. Friends I talked to—particularly foreigners who, like me, hail from warmer climates—expressed a cautious optimism about the possibility that this year’s winter might be over, that we might have survived another season of monotonous gray overcast and chilling eastern winds. But this glee is often accompanied by a guilty evocation of climate change—how can it not be? The winter has been mild, and maybe it’s just me, but it feels like it’s been getting milder every year since I moved here nine years ago from Jerusalem. The past summer, on the other hand, has seen temperatures reaching record highs, leaving scorched yellow patches in city parks where grass once was, drying up the massive Havel river and therewith immobilizing commercial barges, devastating agriculture, with crops shriveling and animal feed-grains toasted in the punishing sun. Even the proverbial protestant work ethic couldn’t withstand the heat: lacking air conditioning, offices were forced to a standstill and schools declared Hitzefrei—in Germany, when temperatures reach over 30C school is canceled and children sent home—overwhelming sunbaked parents, who’s last resort were often the subsidized public pools (the one in my neighborhood saw 330,000 visitors over the summer.) I spent many of those days by the pool too—what else could I do?—but the warmth, comforting as it was to lounge in, felt ominous. The past summer was a watershed moment. Inconvenient truths imposed themselves on multiple fronts: heatwaves, droughts, floods, fires, and one very grim (though, some would say, not grim enough) UN report. An hour drive from my home, forest fires forced the evacuation of two villages in the outskirts of Berlin, with the smoke reaching the city. In California, climate change found its iconic images in an incinerated mountain town called Paradise—the name made for particularly dreadful headlines—the deadliest and most destructive wildfires California has ever seen, and it found its colluder in Trump, who’s steadfast denial of what has become so self-evident, so painfully glaring, shone a cruel radiance of kinship with a long-lasting, if somewhat more oblique, collective complicity. Is denial really any different from indifference? Isn’t my own denial purchased at the price of a biodegradable trash bag here, a recycled puffer jacket there? The solutions offered seem broken, ridiculously inept in confronting the scale and gravity of the crisis we’re in.

Part of the problem, it seems, has to do with the challenge of both perceiving and representing troubles of such magnitude—changes and shifts taking place both at the molecular and the planetary scale—and reconciling these with the mundanity of our everyday life. It’s difficult to imagine our actions—driving a car, taking a plane, purchasing another product or having coffee-to-go from a disposable cup—as irredeemably toxic, to relate them with the constant increase of typhoons, heatwaves, wildfires, ocean acidification, and with the carcasses of bleached reefs.

As I sat on a bench near our home, the soft mid-winter sun washed over my closed eyes. But all I could think of was an essay I just finished reading by Emily Raboteau, where she asks “How to reconcile these twin feelings of pleasure in the city’s enjoyments and terror of its threats? I have learned” she writes “that the world is running out of sand; that every second we’re adding four Hiroshima bomb’s-worth of heat to the oceans”1. She thinks of an hourglass, of her kids.

It’s difficult not to feel utterly helpless when confronted with this reality, knowing that individual action is but a drop in quickly rising, acidifying, ocean waters, that the problem is systemic, and far removed by orders of magnitude from the influence of individuals. The genie, it seems, has long escaped the bottle, and we’ve been left searching in the dark for an emission cap. But a realist fatalism can be as paralyzing, and as harmful, as denialism. So, what is to be done?

Richard Frater, Stop Shell (live rock version), 2018, fossilised coral, 3D printed macroscopic graphs, coral organism, marine aquarium, bio-media, plexiglass, 1460 x 400 x 400mn, Installation view, Michael Lett, Auckland

New Zealand born, Berlin-based, artist Richard Frater has devoted much of his work during the past five years to exploring human complicity in climate change, it’s visual culture and governing logic, but also—no less importantly—modes of resistance, nurture, action, and co-habitation, however fleeting. I’ve known Richard for nearly as long as I’ve lived here. We met at the Berlin University of the Arts, where I was a student of Hito Steyerl’s, who’s open class he would attend.